On September 10, 2020, the Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA) released its internal child fatality review report for 2019. This report raises many issues and concerns. Some relate to the scope and coverage of the report. Others concern the cause and manner of death, the existence of families with repeated CFSA involvement that nevertheless have a child death, the predominance of large families as a correlate of child deaths, and the suggestion that unrelated adults in the home may have perpetrated a child fatality.

Child fatality review is an important way for an agency to assess the quality of its work. CFSA states in the report that “the fatality review process is one of CFSA’s strategies for examining and strengthening child protective performance. It provides the Agency with specific information that helps to address areas in need of improvement and to identify any systemic factors that require citywide attention–all with the goal of reducing preventable child deaths.” But the goal of child fatality review should be broader than reducing child deaths. Child fatalities should be seen as the tip of the child welfare iceberg. For every child who dies, there may be many others who are left in abusive or neglectful homes with no monitoring or support.

There are two child fatality review reports issued in the District. The District of Columbia’s Child Fatality Review Committee (CFRC) is located in the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. CFRC reviews all deaths regardless of cause of all District residents from birth through 18 years, as well as the deaths of youths aged 19 to 21 who were known to child welfare within four years of the fatal event or those known to intellectual and disability services or juvenile justice programs within two years of the fatal event. Each year CFRC reports on all the fatalities reviewed in that year, but these fatalities could have occurred in any previous year. In the most recent report, on 104 cases reviewed in 2018, the deaths reviewed were from 2014 through 2018.

CFSA’s internal child fatality review reports are based on information gathered by the CFSA’s Child Fatality Review (CFR) unit and recommendations developed by the agency’s Internal Child Fatality Committee (ICFR). These reports focus on a smaller subset of child fatalities–all known fatalities of children whose families were known to CFSA within five years of the child’s death. In the past, the report included all fatalities reviewed in each calendar year. As stated in last year’s internal fatality review report, which has been removed from the CFSA website: “Historically, every CFR annual report has also included review data outside of the calendar year, depending on when the CFR Unit received notification of a child’s death. For [Calendar Year] 2018, reviews included fatalities from years 2015 to 2018.” However, the new report, includes only those fatalities that occurred during 2019. This is only 13 of the 33 fatalities the Committee reviewed during 2019, as the agency explains in a footnote. The other 20 fatalities reviewed occurred in previous years and will therefore never be included in a CFSA child fatality report unless the previous practice of including deaths from previous years is reinstated.

Cause and Manner of Death

Of the 12 fatalities for which cause and manner were known, the causes were equally divided between maltreatment, natural causes, non-abuse homicides, and accidents.

- The cause of death was abuse or neglect by a caregiver for three of the children who died in 2019, 25 percent of the 12 children whose cause of death was known. All of these children were under the age of three. For two of these children the cause of death was abuse by blunt force trauma. The other child died of fentanyl poisoning due to neglect.

- Of the 12 children with a known cause of death, three (or 25 percent, died of natural causes. Two of these were children between one and five years old, while the third was a young adult over 18.

- Non-abuse homicides accounted for 25 percent of the fatalities in CY 2019. All of the victims were males living in Ward 8. One was aged 11, another was 16, and the third was 20.

- All three accidental deaths were infant fatalities and all involved unsafe sleeping arrangements.

Demographic Characteristics

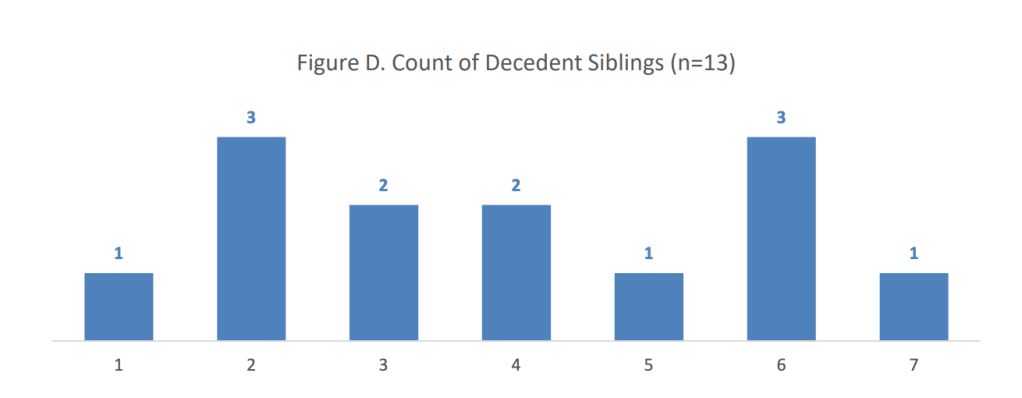

The children who died disproportionately resided in Ward 8 (seven children), Ward 7 (four children), Ward 5 (one child), and Maryland (one child). All of the children who died were African-American. None of these facts are surprising since they reflect the demographics of CFSA’s clients. Most of the children were living at home at the time of the fatality, except two that were living with relatives. All of the children who died had siblings. Nine of the decedents (about 69 percent) had three or more siblings; seven (54 percent) of them had four or more siblings, and four had six or more siblings. Many of the siblings were half-siblings. Twelve of the 13 decedents had at least one-half sibling.

CFSA History

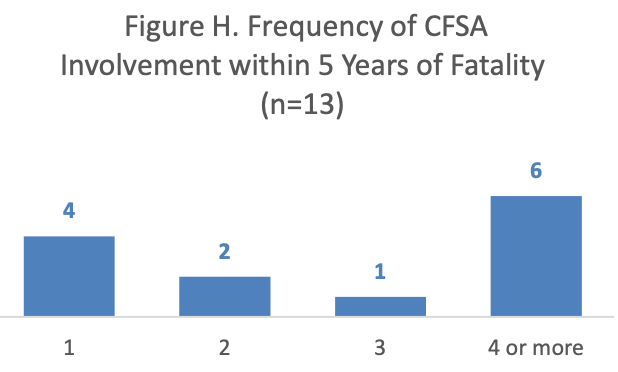

Over three quarters of the decedent’s families (10 families) had an open case or investigation within five years of the fatality. The other three families had one or more screened-out referrals only.

- Six families had four or more reports to CFSA within five years of the child fatality. Nine families had two or more reports.

- Eight families had at least one CPS investigation; of these families, one had a total of 10 investigations, another had seven investigations and two had five investigations.

- All of these investigated families had at least one substantiated allegation of abuse or neglect. Most substantiations were for neglect; the neglect categories with the most substantiations were inadequate supervision and caregiver incapacity. There were two substantiations for physical abuse and two for “mental abuse.”

- Of the eight families that had a CPS investigation, Family Assessment, or case closed within five years of the fatality, the time between investigation or case closure and the fatality ranged from four to 13 months.

Four of the 13 decedents’ families (31 percent) were involved with CFSA at the time of the child’s death. All of these families had open Permanency (foster care) cases. According to additional information provided by the agency, one of these children, a three-year-old, was in foster care with a relative. Her death was classified as an abuse homicide due to blunt force injuries, but it was not known if the injuries were caused by the relative or another adult in the home. Another decedent, a 17-year-old male, had run away from foster care and been missing for 17 days when he was shot to death. The other two decedents were living at home at the time of their deaths: one was an accidental death (asphyxia due to unsafe sleep) and the other decedent’s manner of death was undetermined. According to additional information provided by the agency, in both of these cases the non-custodial parent lived in a different household and had an open permanency case for the decedent’s half-sibling.

CFSA’s Recommendations

CFSA’s Internal Child Fatality Review Committee (ICFR) makes recommendations based on the information it reviews; these recommendations are approved by the Agency Director. There were surprisingly few recommendations based on 2019’s child fatalities. One of them calls for the agency to “ensure that practitioners identify and evaluate all adults living (or potentially living) in the same home as a child in foster care.” CFSA’s Communications Director told Child Welfare Monitor DC that a three-year-old decedent in kinship care died of blunt force trauma that may have been inflicted by an adult that was living in the home. Based on the recommendation, we can assume that adult was not evaluated as part of the foster care licensing process. During my tenure as a social worker in foster care, foster parents (including kin caregivers) not informing their licensing agencies of adults living in the home was a common concern. Often this information is purposely kept from social workers because the adult (often a boyfriend) has a criminal or child abuse record that would prevent the home from being licensed. To address this problem, CFSA plans to have supervisors “continue to work with social workers to identify adults who live in or spend significant time in the home and ensure all adults are evaluated.”

Analysis

This report raises many issues and concerns. These include the exclusion of 20 cases from years prior to 2019, the many children who died of causes that might have been prevented by CFSA, the deaths of children in families with long histories of CFSA involvement, the large size of many decedents’ families, and the possible role of an uncleared adults in the home in a child fatality.

Scope and Coverage of Report: While the ICFR Committee reviewed 33 fatalities during 2019, the report covers only those 13 fatalities that actually occurred in 2019; all of the other 20 occurred in prior years, mostly 2017 and 2018. Unless CFSA returns to its earlier practice of including all fatalities reviewed in a calendar year in that year’s report, these 20 fatalities will never be covered in a future report. This is the first year the ICFR left out all deaths that did not occur in the same year as they were reviewed. Like the citywide Child Fatality Review Committee, until this year the ICFR reported on all of the fatalities it reviewed in a calendar year–not just the ones that occurred in the same year they were reviewed. Leaving out more than half of the fatalities of children known to CFSA in its annual fatality report every year deprives the public, policymakers and stakeholders of crucial information that, if acted upon, could help prevent fatalities and harm to children in the future.

Lack of Case Detail: The lack of detail on the individual cases is a major problem in making sense out of the information provided in this report. Statistical data on such a small number of cases is of limited utility, but knowing the history of CFSA involvement in each case would enable readers to pinpoint the opportunities that may have been missed to prevent the fatality and lessons for the future. The public should know such details, as long as personal information redacted. Some states, like Texas, Florida, and Washington are required to post fatality reviews for children who died of abuse or neglect following involvement with the child welfare agency, as described by Child Welfare Monitor. Detailed fatality case studies on child deaths with agency involvement (without identifying information) are provided in other jurisdictions by independent agencies like the Office of the Child Advocate in Rhode Island and Connecticut and the Inspector General for the child welfare agency. Legislation to establish an independent Ombudsperson for CFSA was introduced in 2019 by Councilmember Brianne Nadeau. Such fatality reports were not included in her original legislation, which was never put to a vote, but could be added to the next version.

Cause of death and preventability: The cause and manner of death were known in 12 of the 13 cases and were distributed evenly between four categories–natural causes, accidents, abuse homicides, and non-abuse homicides. The deaths from natural causes were very likely not preventable by CFSA action. Deaths in the other three categories, however, could possibly been prevented if CFSA had responded differently to these families when they came to the agency’s attention. Clearly the fatalities from abuse or neglect raise the question of whether CFSA terminated its involvement without ensuring that the maltreatment that led to the initial allegation had ended. Accidental deaths can reflect neglect. For example, all of the accidental deaths in this report reflected unsafe sleep practices..

Preventability of non-abuse homicides: We don’t know the details on the tragic deaths of an 11-year-old, a 16-year-old and a 20-year-old of non-abuse homicide. Was the youngest victim (most likely an innocent bystander and possibly the case that appeared in media reports in June 2019) exposed to violence because of the lifestyles of the adults who were caring for him? Were the two older youth themselves involved in violence and criminal activities, as is the case for many young victims of violence? Three of the families were involved with the Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services (DYRS), suggesting that one child (perhaps not the decedent) in those families was involved in illegal activities. I spent five years working as a social worker in foster care and almost four years serving on the citywide Child Fatality Review Committee. In this work I have seen numerous examples of young people who became involved in crime and violence after growing up in families that were repeatedly involved in child welfare due to drug activity, domestic violence, mental illness, and abusive or neglectful parenting. Cases were opened and closed, and children were in and out of foster care, but none of these interventions resulted in any substantial change in parental behavior. Perhaps some of these tragic deaths could have been prevented if better, more intensive and long-lasting services had been provided to the parents, or if the children had been removed from these homes after their parents failed to take advantage of offered services.

Families with Repeated CFSA Involvement: It is clear from the extensive history of some of these families with CFSA that the agency is failing to identify some children who are in danger in their homes. Some investigations may fail to identify the family’s most severe problems; some cases may be opened for foster care or in-home services but may close before the parents succeed in changing their behaviors. CFSA requires a “4+ staffing” for all families that have four or more allegations with the last report occurring within the past 12 months. There was concern in previous years that families with child fatalities had more than four allegations but there was no documentation of a 4+ staffing. As a result, ICFR in 2018 recommended that the agency “make 4+ staffings more consistent,” a recommendation that was reported as “complete” in this year’s report. CFSA reports that five of the families with a child fatality in 2019 were eligible for a 4+ staffing. Of these families, four were documented as receiving such a staffing, but there was no explanatory documentation for the family that did not receive one. If the agency is indeed more consistently holding these meetings, it may be time to evaluate their effectiveness.

Unknown adults in a kinship home: Information provided by CFSA indicates that one of the abuse homicides was perpetrated in a kinship home and that it is not clear whether the perpetrator was the relative or another adult in the home. Evidence suggests that many abuse homicides are perpetrated by other adults living in the home, particularly nonparent partners, as described in Within Our Reach, the report of the Commission to Eliminate Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities.

Large families: There is considerable evidence that the deceased children tended to come from larger families. Not only did 70 percent of the decedents have three or more siblings but more than half of the decedents had four or more siblings. The average number of children in a family is only 1.9 in the United States. Large numbers as well as close spacing of children are correlated with more abuse and neglect. Many of these mothers started having children as teenagers. Often, the medical providers used by low-income women lack access to the more modern, effective modes of contraception such as Long Acting Reversible Contraceptives (LARC’s) at all, or require a second visit to obtain these methods.

Recommendations

- Cover all fatalities reviewed: CFSA should return to its previous practice of covering all deaths of children known to CFSA within five years–not just those that took place in the year of review. This would probably at least double the number of cases included, providing a much larger basis for making conclusions.

- Provide detailed case studies by a neutral party: The public needs to have access to a detailed case study of each fatality in a family with which CFSA had recent involvement. Such a case study would include a chronology of agency involvement and a description of touchpoints where the agency could have done something different and perhaps averted the death. This is particularly important for legislators, who might want to take action to avert future deaths, and for members of the media, who are often the ones that make the public aware of gaping holes in our child safety net. Ideally, such an analysis would be performed by a neutral party, such as the child welfare ombudsman’s office that was proposed last year.

- Pay attention to those with repeated CFSA reports: CFSA should assess the nature of the 4+ staffings to determine whether they are having any impact on families with multiple allegations, whether the current guidance for such meetings needs to be changed, and whether other measures should be implemented to ensure that families with repeated allegations get more attention.

- Evaluate all adults in the home: The IFRC suggested that the agency “ensure that practitioners identify and evaluate all adults living (or potentially living) in the same home as a child in foster care.” To implement this recommendation, the report states that CFSA plans to have supervisors “continue to work with social workers to identify adults who live in or spend significant time in the home and ensure all adults are evaluated.” More specific guidance may be needed for supervisors and workers as to how to identify such adults.

- Increase access to effective birth control methods: The large size of many decedents’ families highlights the need for policies to increase access to modern, effective and long-acting birth control options for all women in the District. Some of the saddest moments in my life as a foster care social worker came from hearing that a mother struggling to get her existing children back from foster care was pregnant again. Clearly expanding access to family planning is in the bailiwick of the Department of Health (DOH) rather than CFSA. However, even in the absence of DOH initiatives, CFSA could collaborate with DOH to ensure that the parents involved in cases have access to effective contraception as soon as their cases are opened and are educated about the deleterious effects of close child spacing and large families, and that family planning is included in case plans.

Studying fatalities among children known to a child welfare agency is an important way to find out how well an agency does its job of protecting children and to suggest changes to protect children better in the future. CFSA’s review of a limited number of child fatalities (probably less than half) among children known to CFSA in FY 2019 suggest that the agency could have done more to identify and protect some children in danger. And for every dead child, several more may be suffering from abuse and neglect that will poison their future. Leaving out over half of the children whose deaths were reviewed in 2019 just because they died in previous years is an unnecessary loss of information that could be crucial in saving lives in the future. And without a detailed study of each case, it is impossible for legislators and members of the public to evaluate whether CFSA did all that it could to prevent these deaths and protect the many other children in these homes.

This post was modified on October 15, 2020 to incorporate new information provided by CFSA on the families of decedents who had open permanency cases as well as to modify a statement regarding the scope and coverage of the report.

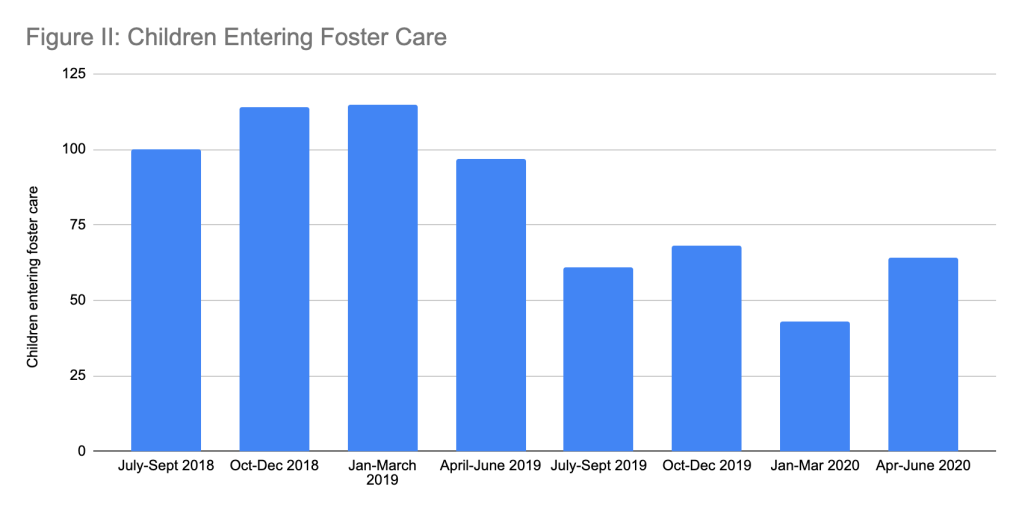

Social distancing is essential to break the back of the coronavirus pandemic. But for children who are at risk of abuse and neglect, social distancing can mean being cut off from the people who might see and report their situation. The District’s Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA), like other agencies around the country, has recognized the problem. However, its response should be strengthened in order to check in with isolated children before schools close on May 29.

Social distancing is essential to break the back of the coronavirus pandemic. But for children who are at risk of abuse and neglect, social distancing can mean being cut off from the people who might see and report their situation. The District’s Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA), like other agencies around the country, has recognized the problem. However, its response should be strengthened in order to check in with isolated children before schools close on May 29.