This post summarizes the results of my analysis of CFSA’s FY2023 data, compared to the data from FY2022 and previous years. Except when otherwise noted, the data is drawn from the Public Dashboard of the District of Columbia’s Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA), which provides data, updated quarterly, on the agency’s essential functions. My analysis showed a large increase in hotline calls in the last year, but a decrease in the number of investigations and substantiated claims of abuse or neglect. The foster care and in-home caseloads continued to fall, with a precipitous drop in the opening of in-home cases in particular. An important finding was the decline since 2019 in the number of in-home and foster case opened as a proportion of substantiated investigations. Taken together, the data suggest an agency that is withdrawing its core mission of responding to abuse and neglect in favor of new initiatives that are more in accord with the current ideological climate in child welfare.

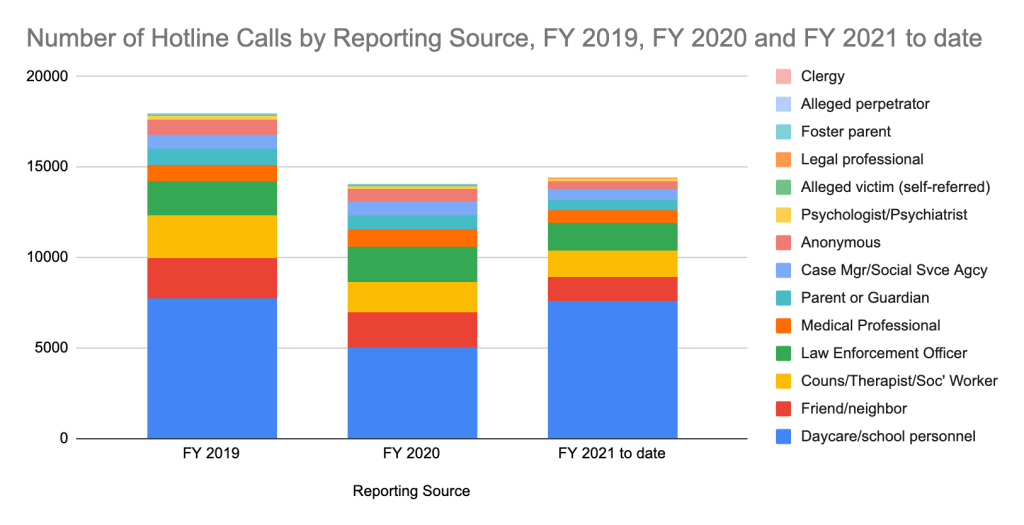

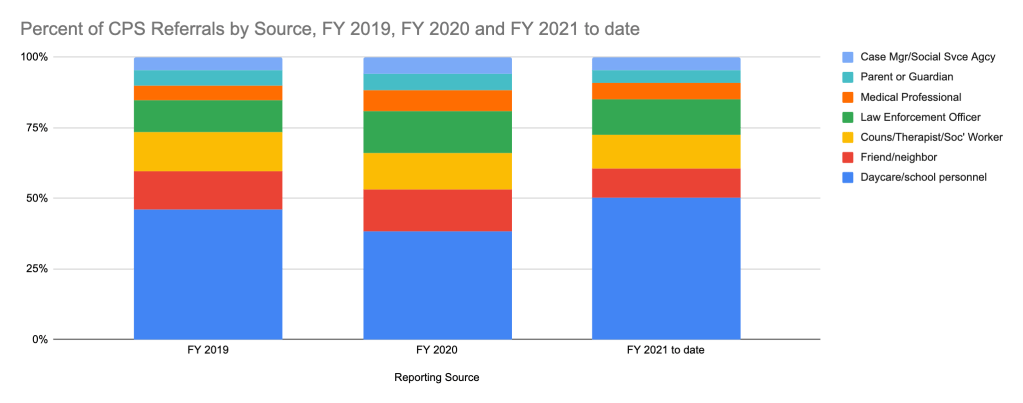

There were 20,246 calls to the CFSA hotline (called “referrals” by the agency) in FY 2023. About 51 percent of the referrals came from school and daycare personnel; that share has increased to more than its pre-pandemic level of 42.9 percent in 2019. Nationally, teachers, made only 20.7 percent of referrals in FY2022. The District’s very different reporting pattern may reflect its educational neglect law, which requires teachers to make a report when a child has more than ten unexcused absences in a year.

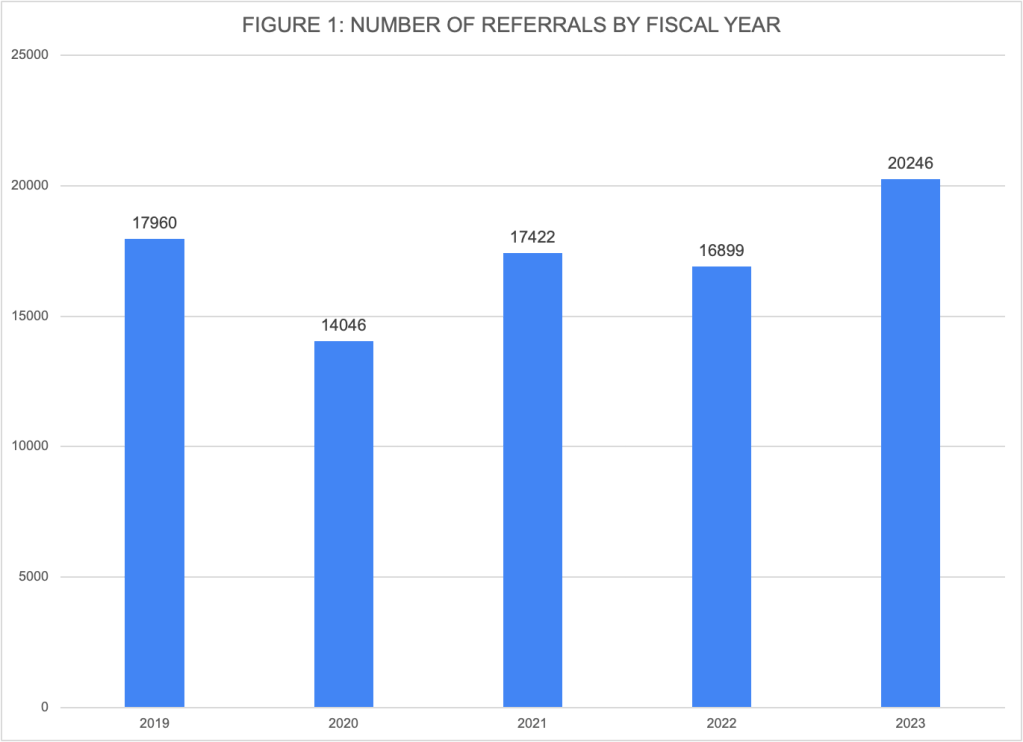

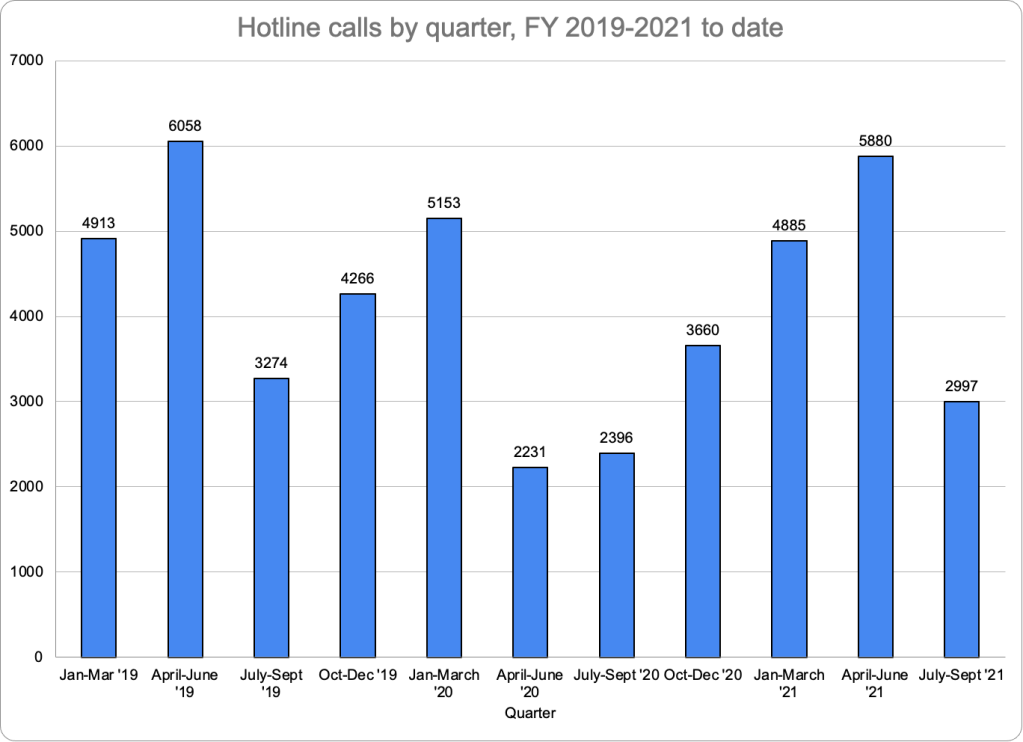

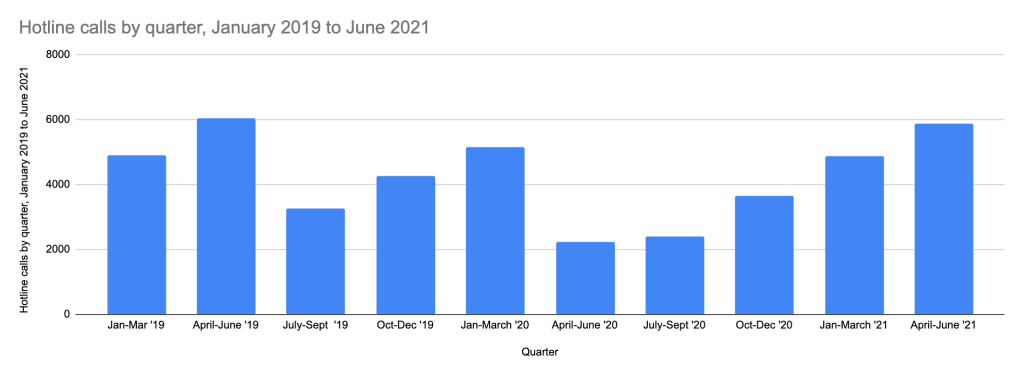

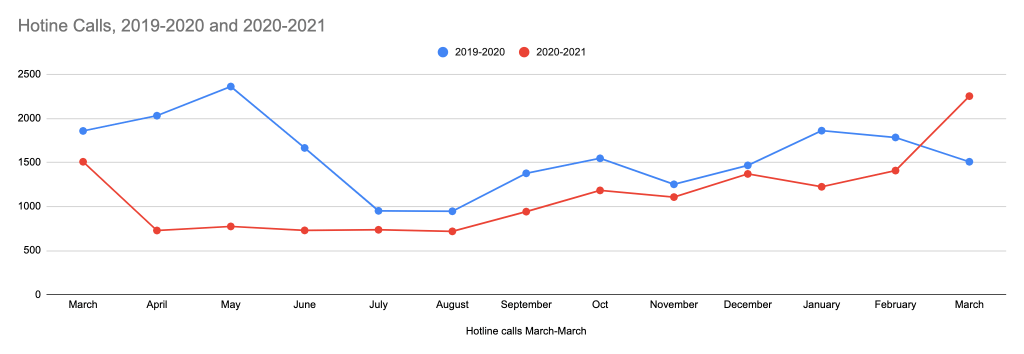

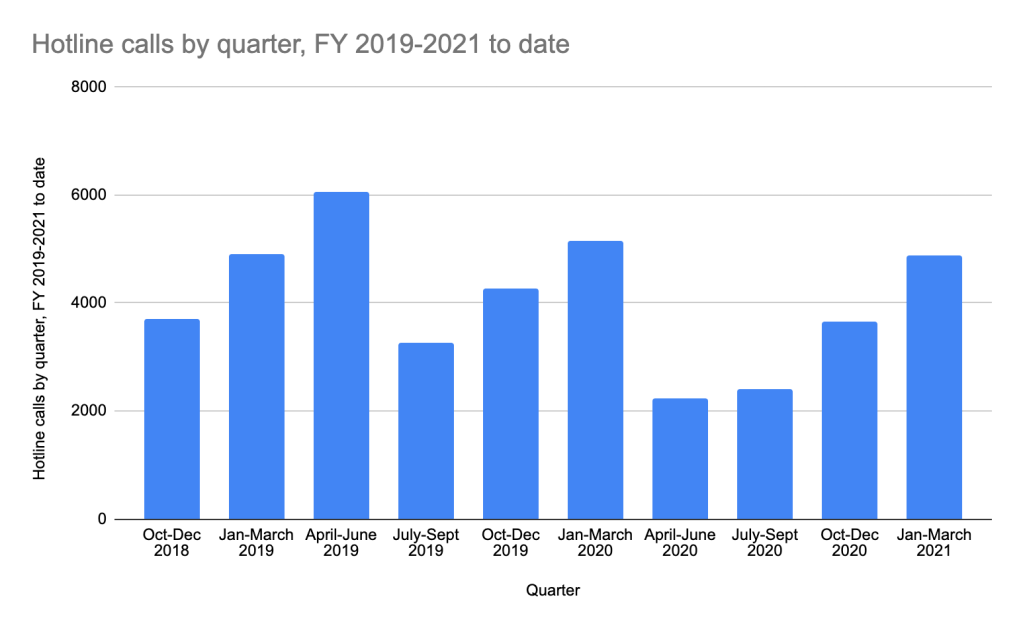

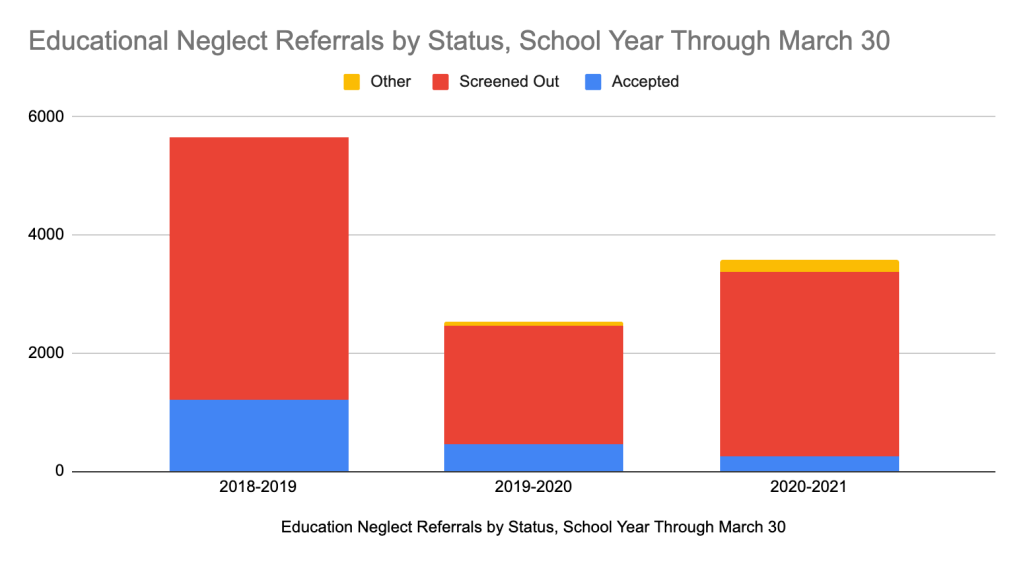

Figure 1 shows the precipitous drop in referrals during the pandemic year of 2020, followed by an increase in FY2021, and a slight dip in FY2022. The total of 20,246 calls to the hotline in FY2023 was 20 percent above the total of 16,899 in FY2022 and even eclipsed that of the year before the pandemic. Most sources increased their reporting in FY2023, but much of the increase came from school and childcare personnel, who made 10,329 reports in FY2023 compared to 8,389 in FY2022. It is not clear why referrals increased so much in FY2023.

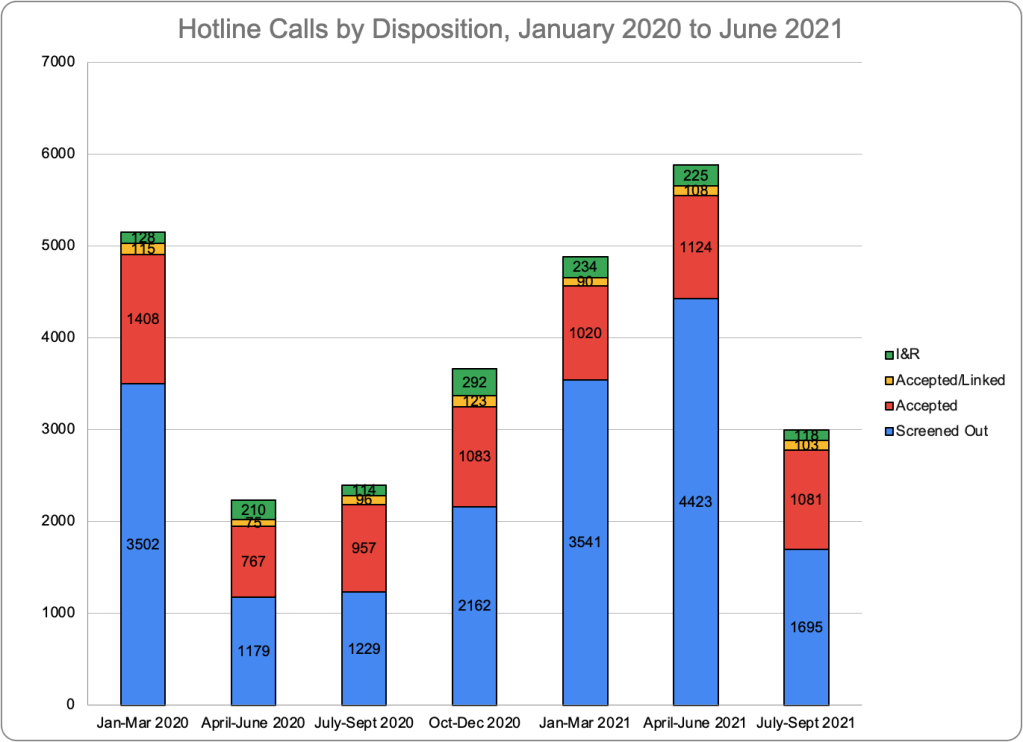

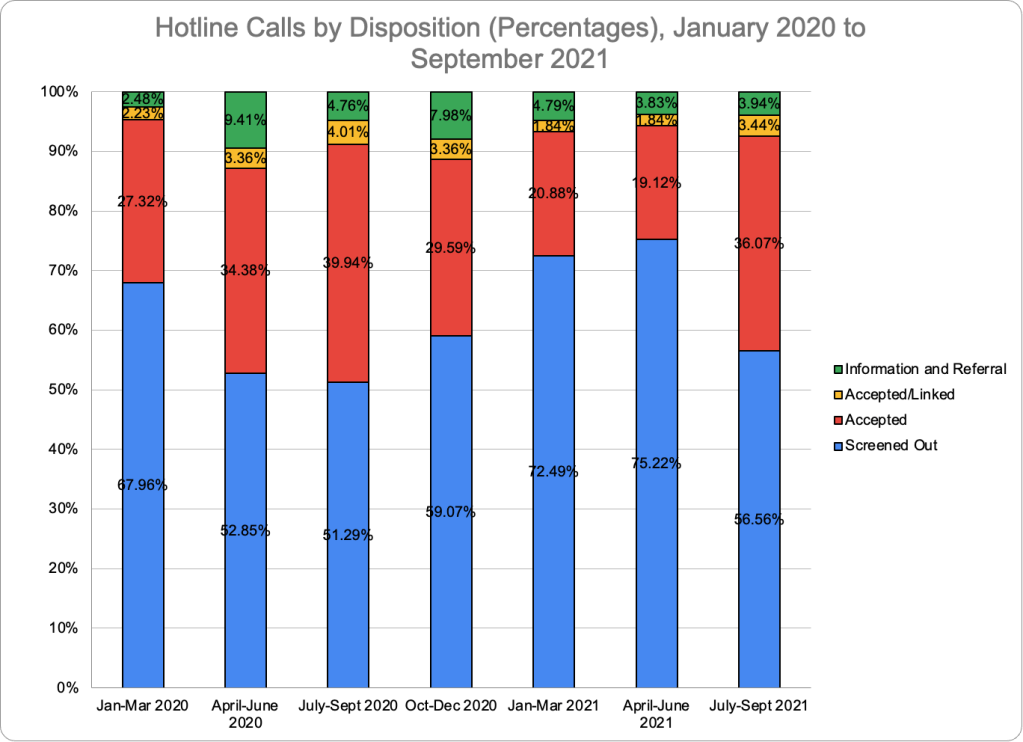

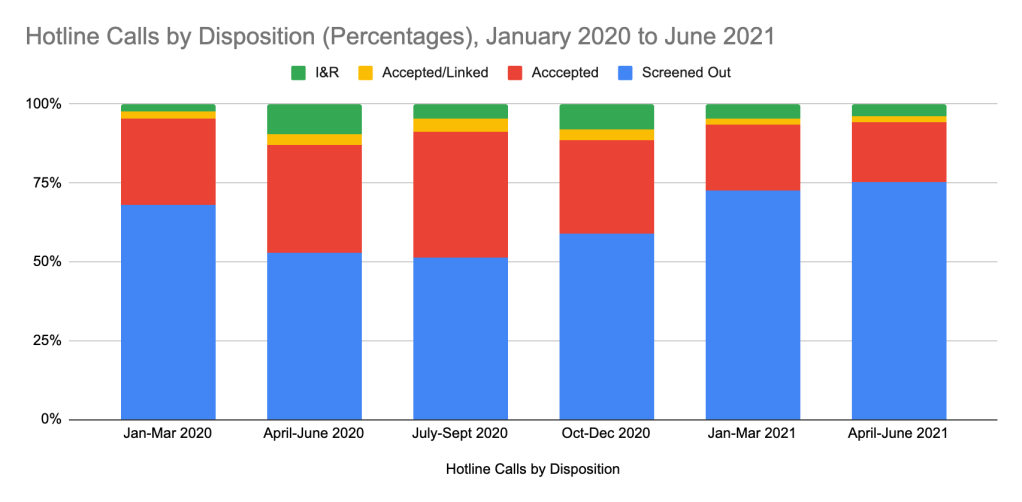

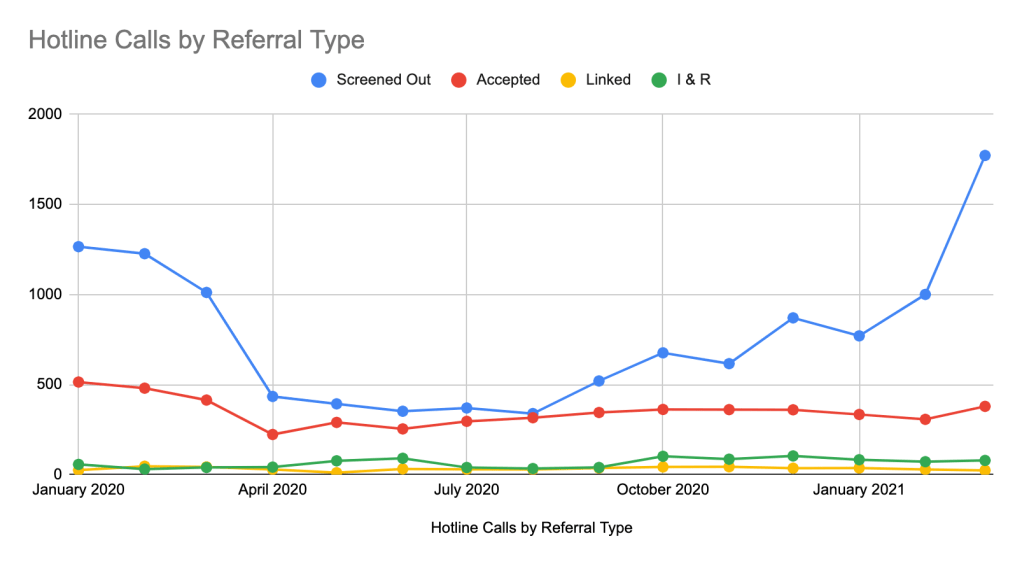

CFSA responded to the increase in referrals by screening out a larger percentage of these calls and accepting a smaller percentage for investigation. Out of the 20,246 referrals received in FY2023, CFSA hotline staff screened out 11,540 or 73.7 percent, compared to the 68.3 percent of referrals they screened out the year before, as shown in Figure 3. And they accepted only 19.3 percent, as compared to the 26.2 percent they accepted the year before. (Referrals not screened out or accepted were linked to an existing investigation or redirected to another agency). Hotline staff actually accepted significantly fewer referrals for investigation in FY2023 than in FY2022 despite the increase in referrals–a total of 3,902 accepted referrals in FY2023 compared to 4,429 the previous year, as FIgure 2 shows.

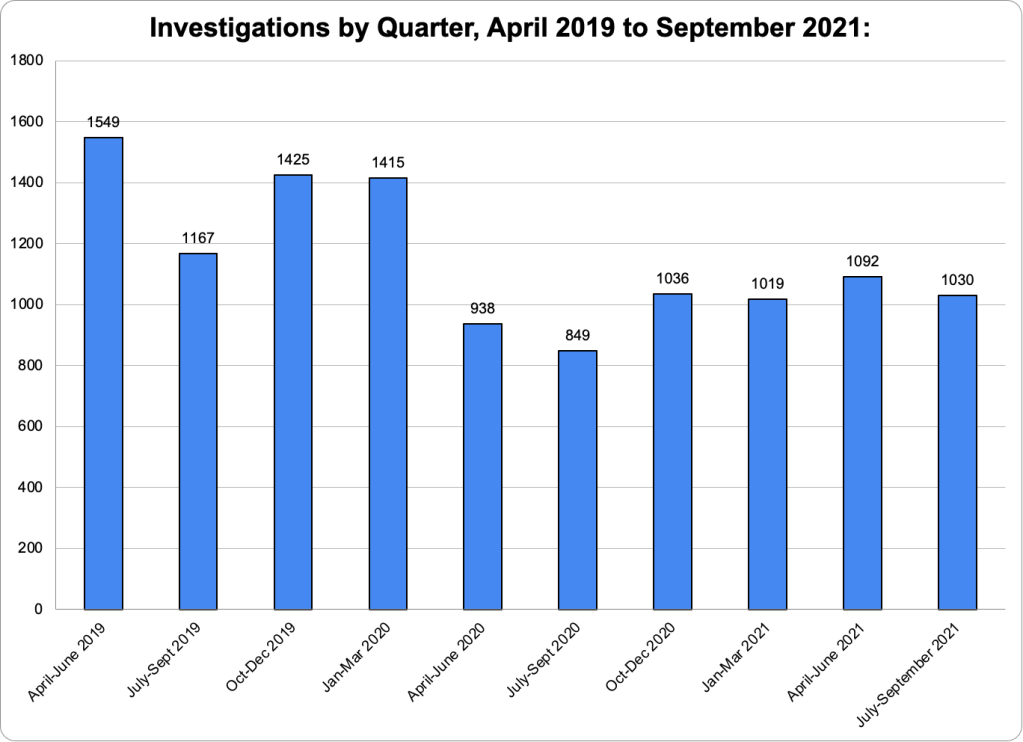

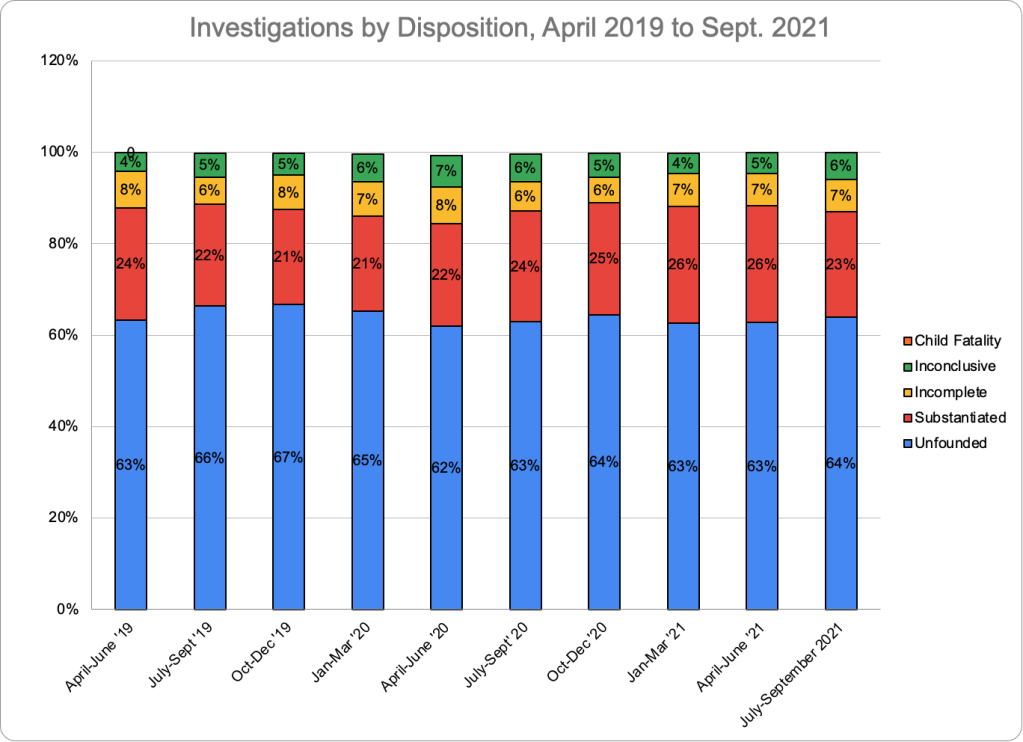

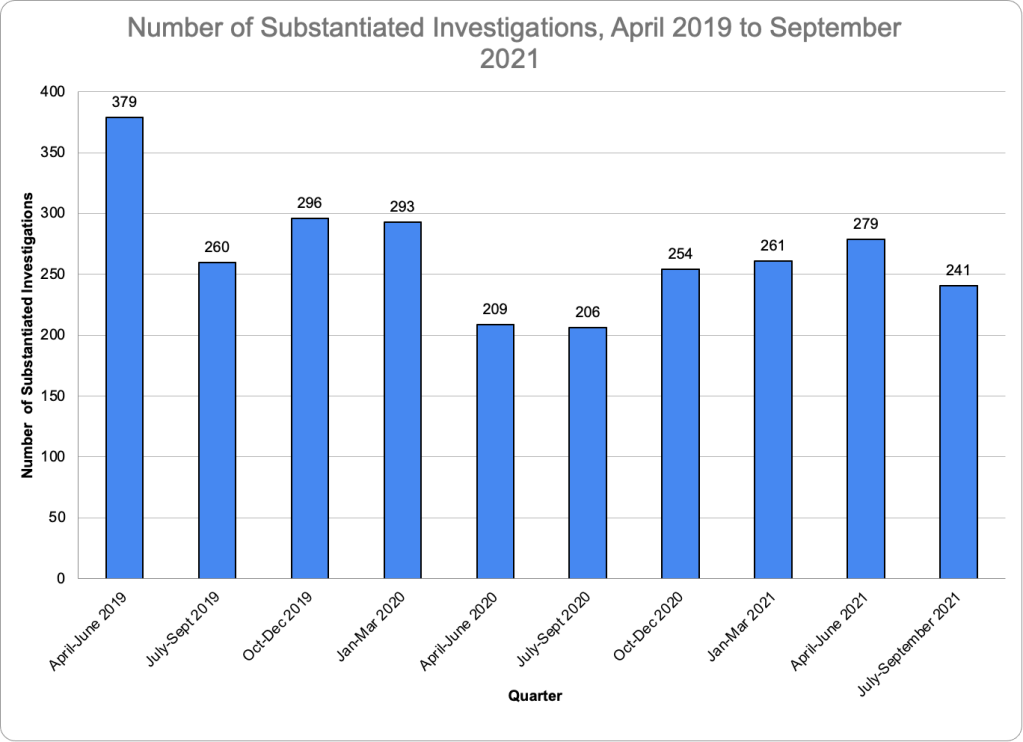

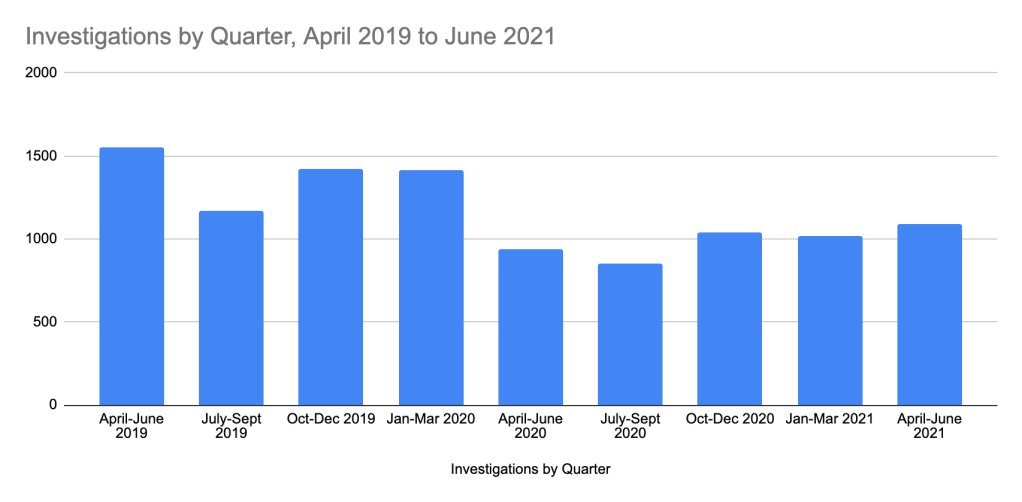

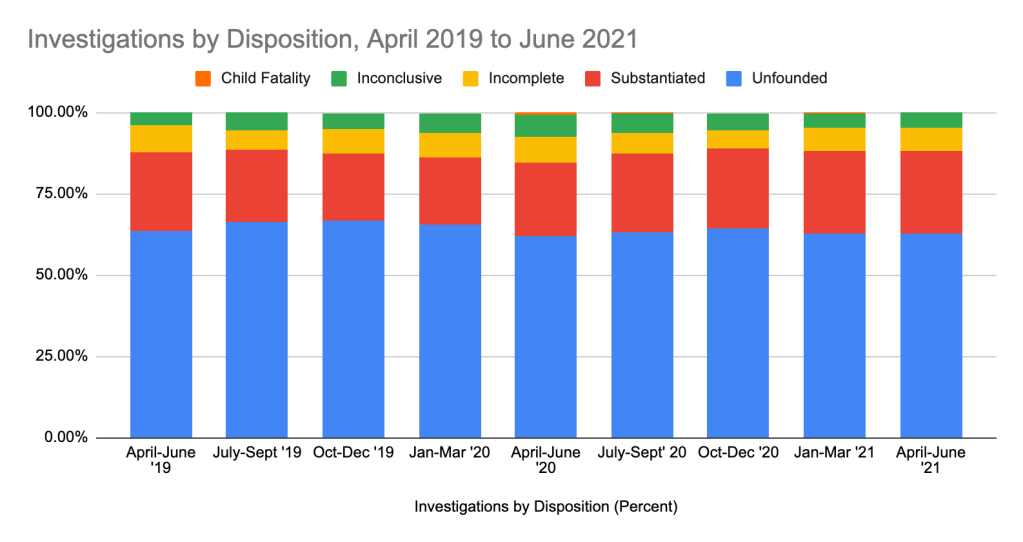

With fewer referrals accepted for investigation, there were naturally fewer investigations, as the height of the bars in Figure 4 shows.* The number of investigations that was substantiated (meaning the allegation of maltreatment was supported by the investigation) decreased from 861 in FY 2022 to 799 in FY2023, which was a drop of 7.2 percent. But the percentage of investigations that were substantiated did not change, remaining at about 21.5 percent of all investigations. So the decline in substantiations reflects the decline in the number of investigations initiated rather than a decreasing tendency to substantiate allegations.

Source: CWMCD analysis of data from the CFSA Data Dashboard, https://cfsadashboard.dc.gov/

Substantiated investigations can result in several outcomes, depending on the level of danger and risk to the child or children as estimated by Child Protective Services (CPS). if the child or children are deemed to be at low-or moderate risk, policy dictates that the family be referred to one of the Healthy Families/Thriving Communities collaboratives, nonprofits that are funded by CFSA to provide case management and other services. If the risk is deemed to be high or “intensive,” CFSA opens an in-home case. And if the child or children are assessed to be in imminent danger, the child is placed in foster care or an informal placement with kin or a family friend.**

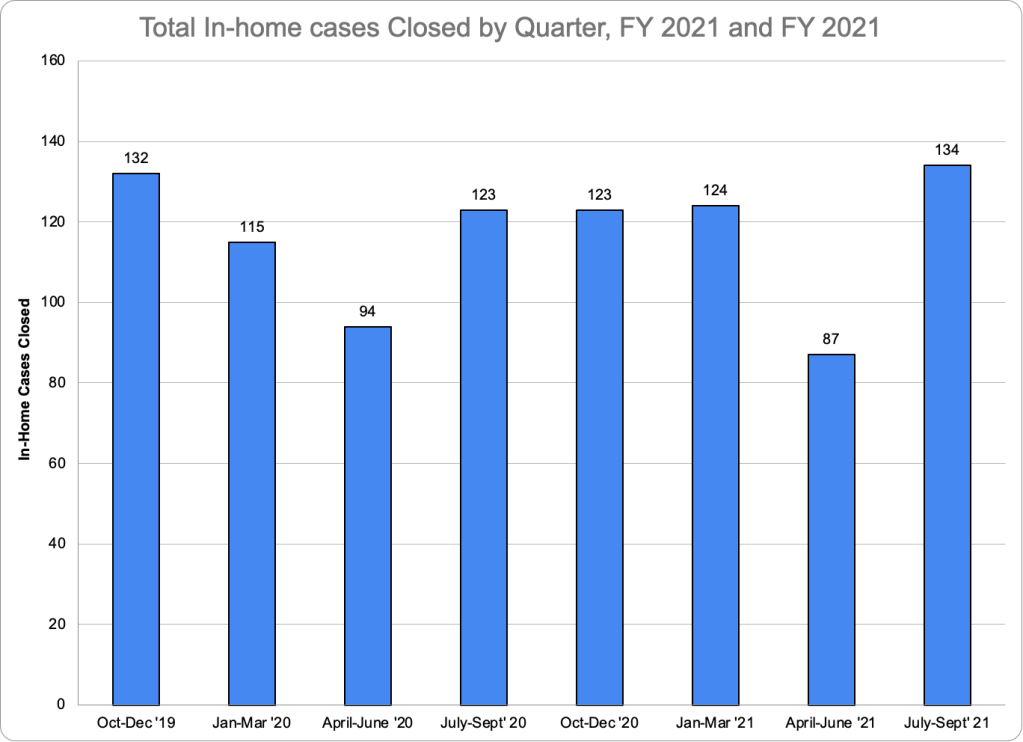

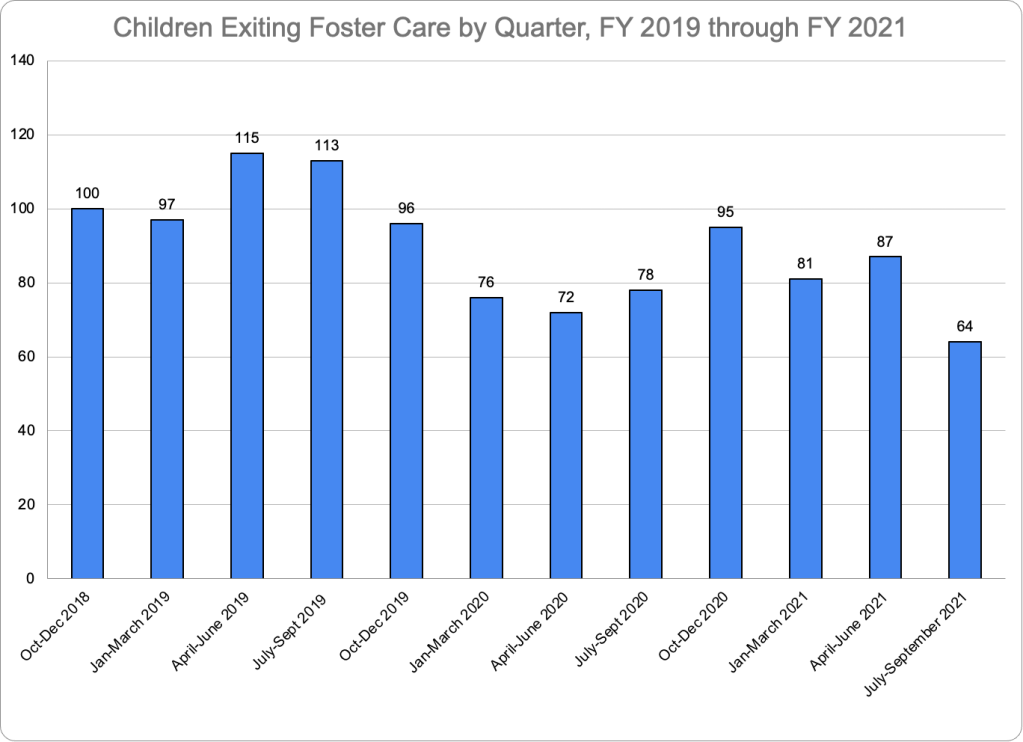

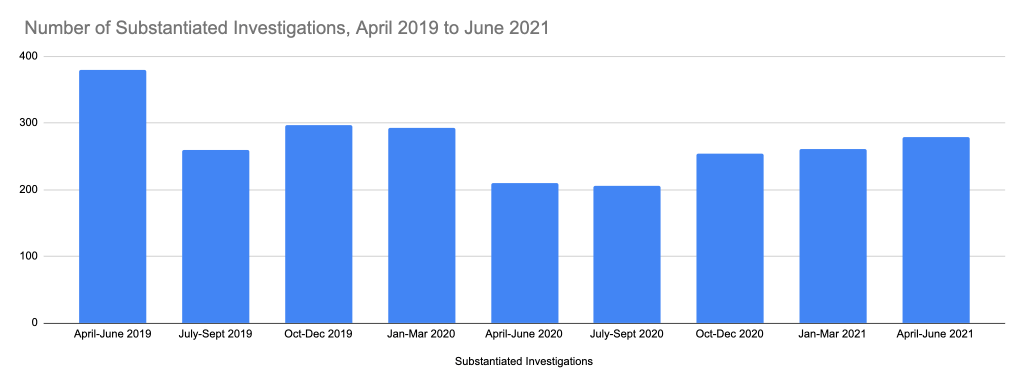

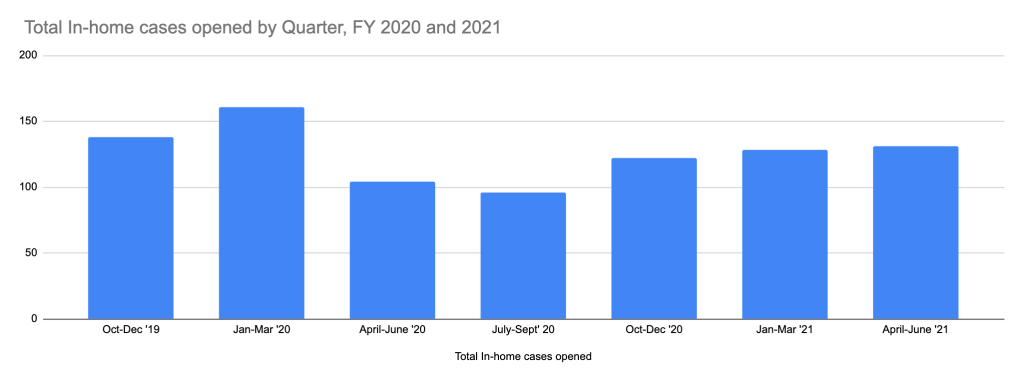

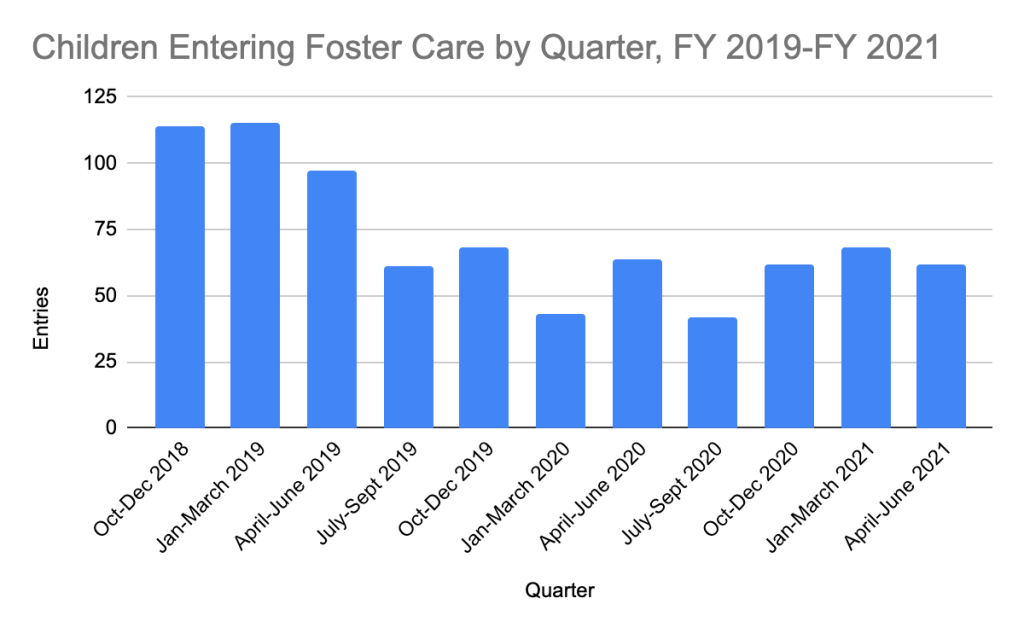

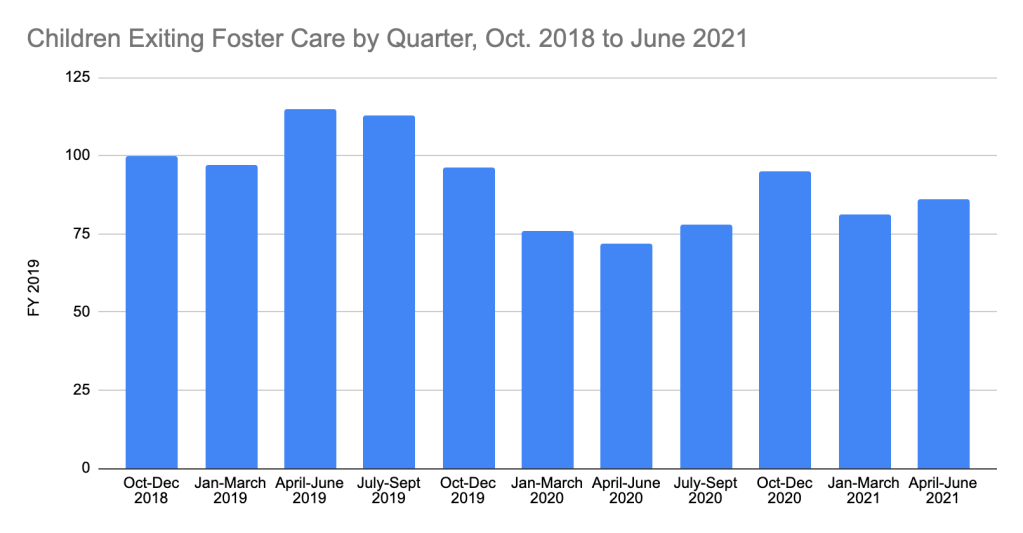

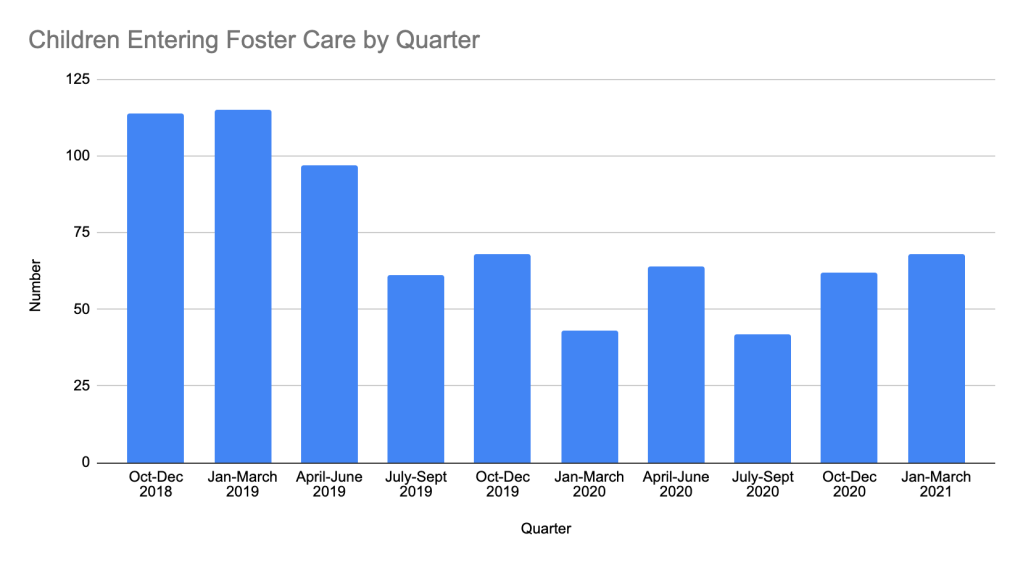

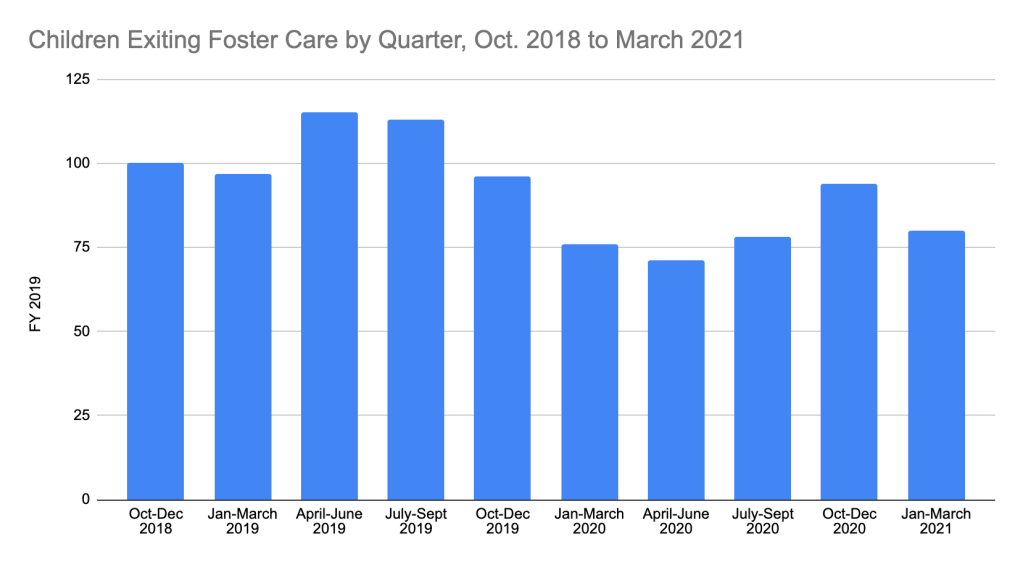

Table 1 shows the number of substantiated investigations, in-home cases opened, and foster cases opened between FY 2019 and FY 2023. The table shows that the number of substantiated investigations has been falling since 2020. In-home case openings fell moderately from FY2020 to FY2022 and dramatically from 463 in FY2022 to 363 in FY2023, a drop of 21.6 percent. Foster care entries, which had fallen rapidly between FY2019 and FY2022, fell less dramatically in FY2023, perhaps beginning a leveling trend after years of rapid decline. The total of in-home cases opened plus foster care entries (in other words, the total number of cases opened) fell from 886 in FY2019 to 542 in FY2023, a drop of 38.8 percent. From FY2022 to FY2023, total cases opened dropped by 18.4 percent. The number of In-home and foster care cases opened as a percent of substantiated investigations over the five-year period has dropped considerably since 2019, from 88.2 percent in FY2019 to 67.8 percent in FY2023, indicating a reduced likelihood of opening a case when an allegation has been substantiated.

Table One: Substantiations, In-Home Cases Opened and Foster Care Entries, FY2019 – FY2023

| Fiscal Year | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Substantiated investigations | 1004 | 1035 | 920 | 861 | 799 |

| In-Home Cases Opened | 499 | 500 | 442 | 463 | 363 |

| Foster Care Entries | 387 | 217 | 251 | 201 | 179 |

| Cases opened (In-Home Cases Opened Plus Foster Care Entries) | 886 | 717 | 693 | 664 | 542 |

| Cases opened as a percent of substantiated investigations | 88.2 | 69.3 | 75.3 | 77.1 | 67.8 |

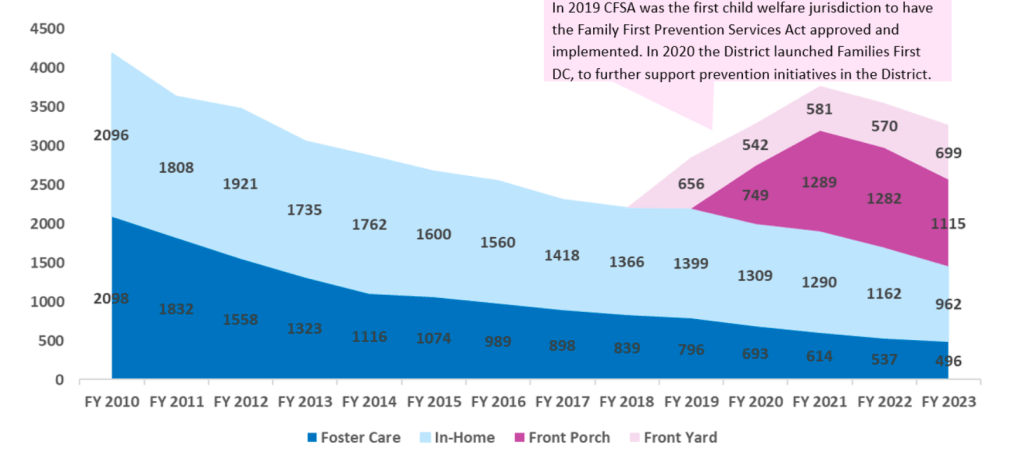

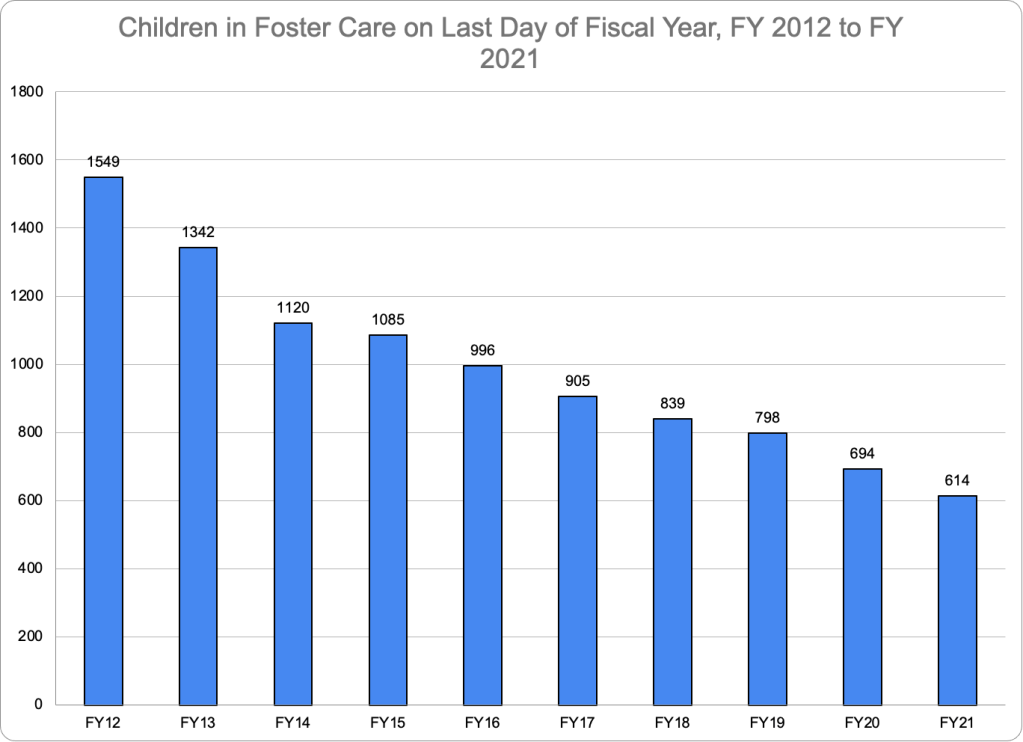

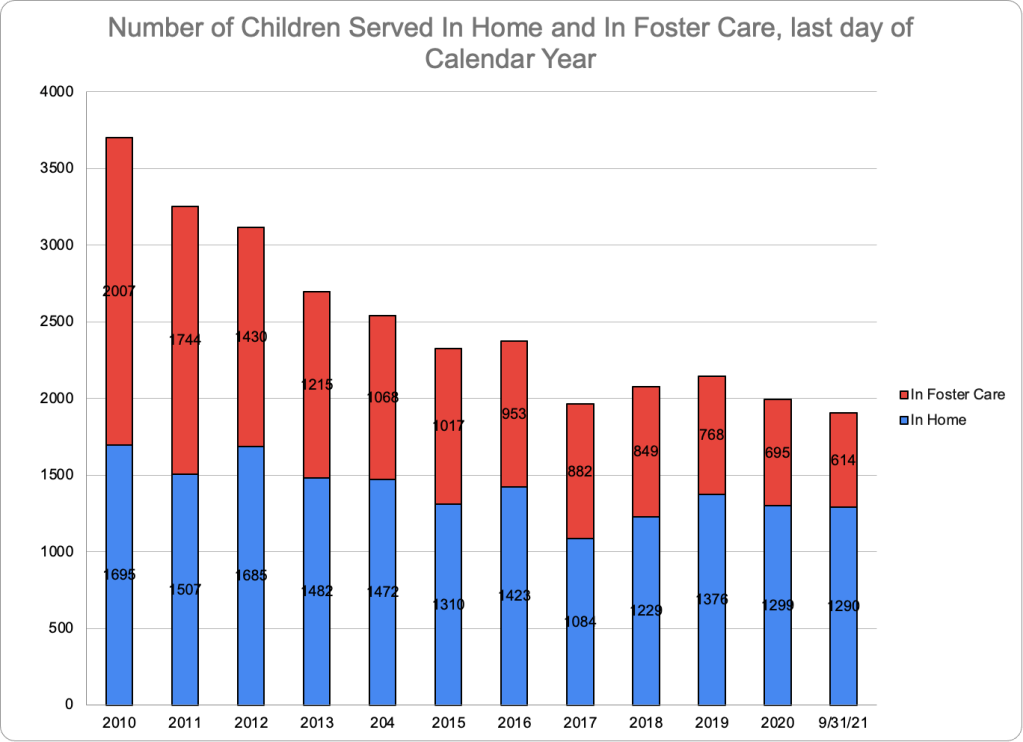

For a longer-term view, Figure 5 shows the number of children served in-home and in foster care on the last day of the fiscal year (September 30), using historical data from CFSA’s most recent Annual Needs Assessment.*** In 2010, about as many children were served in foster care as in their homes, but since that time the proportion of children served in their homes has risen, standing at 66.0 percent in September 2023. The foster care caseload has decreased every year and shows signs of starting to level off. The in-home population has also declined over time, though less steadily. The number of children served in their homes, though still much larger than the foster care population, has fallen much faster than the latter in recent years, dropping from 1,290 on September 30, 2021 to 962 on September 30, 2023. The total number of children served in home and in foster care has fallen from 4,194 in FY2010 to 1,458 in FY2023, a drop of 65 percent. And it dropped by a precipitous 33.6 percent between FY 2019 and FY2023. The “footprint” of CFSA, in terms of essential services, has shrunk dramatically.

CFSA is pushing back against any impression that it is serving fewer families and children, as shown in the graphic displayed below from the latest Annual Needs Assessment. To the foster care and in-home populations (the same numbers shown in Figure 5) they add two more populations starting in FY 2019 — children and families they categorize as “Front Porch” and “Front Yard.” The agency defines “Front Yard” as families not yet involved with CFSA “but facing challenges that could put them at risk of coming to the agency’s attention.” It defines “Front Porch” as “families known to CFSA, both with and without an open case.”**** These “Front Yard” and “Front Porch Families” are being served by the Healthy Families/Thriving Communities Collaboratives using CFSA funds, rather than directly by CFSA.

Adding the “Front Porch” and “Front Yard” children to the children served in their homes and in foster care gives the impression that the number of children and families served has not fallen but in fact has increased in recent years. That may be technically true, but there are serious problems with that assertion. First, the total number of children served by the Collaboratives began declining in FY2021, and it is not clear what the future holds. Second, the services provided by the Collaboratives are typically much less intensive (and therefore cheaper) than CFSA’s in-home services. Collaborative case managers are generally not licensed Masters-level social workers and have much higher caseloads than CFSA in-home workers. Therefore, they often do not have the time or the skills to to provide the same level of services. Collaborative services have had a dubious reputation over the years; one of the first things I heard as a social worker at a private District agency managing CFSA foster care cases is how one could not expect any meaningful services from a collaborative. As a matter of fact, CFSA tried to end its contracts with the Collaboratives in FY2018 under the previous director, Brenda Donald. But the outcry from Collaborative staff and community members (perhaps recruited by the Collaboratives themselves) led her to renew the non-competitive contract for the collaboratives.

Third, it is not obviously sensible to divert CFSA funds to families in the “Front Porch,” and especially the “Front Yard,” when the agency is clearly not doing enough for the families currently receiving in-home services. The latest needs assessment focuses on in-home services and is sobering reading. In-home caseworkers responding to a survey reported that the most common barriers that caregivers display (daily parenting behavior, substance abuse, and mental health) barely change between the opening and closing of an in-home case. Only a quarter of the in-home cases reviewed by CFSA’s internal reviewers demonstrated “good progress.” CFSA concluded that the lack of progress in the other three-quarters of cases was due to the lack of parental engagement in services. CFSA’s responses to oversight questions from the Committee on Facilities and Family Services show that of the 503 in-home cases closed in FY 2023 and the first quarter of FY 2024, 214 (or 40 percent) of the families have already been the subject of a hotline call after the case was closed. My study of deaths of children known to CFSA between 2019 and 2021 showed that four of the deaths occurred while an in-home case was open for the family. Three other families had had one or more in-home cases that closed before the children died.

The data analyzed here show that from FY2010 to FY2023, CFSA has been serving fewer families with in-home services and foster care. In the last year, the decline continued even as calls to the hotline increased. During that last year, it is the rejection of a higher number of referrals and the reduced likelihood of opening a case when a referral is substantiated that account for the decrease in families served. But what is the actual cause of these trends?

There is more than one possible explanation for the rejection of more referrals and the opening of fewer cases for each substantiated referral. Like other child welfare agencies, CFSA is struggling with a staffing shortage. Perhaps the lack of staff in all units is constraining the ability to conduct investigations and staff the number of cases that are needed. That could result in hotline workers accepting fewer referrals and CPS workers referring more families to the collaboratives instead of to in-home services.

Another factor that is clearly at play is a changing perception of the agency’s purpose. CFSA’s leadership seems unenthusiastic about its primary mission of responding to child abuse and neglect. Agency management craves a less reactive role, adding the prevention of child maltreatment to the agency’s other responsibilities. As Director Robert Matthews likes to say, and repeated in his oversight testimony, he wants to transform CFSA “from a child welfare agency to a child and family well-being system.” That’s why the agency has gone even further beyond its core mission in its Families First DC initiative, attempting to reach even beyond the front yard to work with any family living in one of the disadvantaged communities where they have funded Family Success Centers that provide a wide variety of services and activities. But the agency seems to disregard the fact that these programs are likely to attract the families that are the least at risk of child maltreatment.

CFSA’s approach is in tune with the messages that are coming from the federal government and the powerful foundations and nonprofits that heavily influence the national child welfare agenda. These organizations disparage the “family policing” functions of child welfare and recommend, if not abolition, a drastic reduction in its traditional functions of investigations, in-home services, and foster care. By being in tune with the Zeitgeist, CFSA puts itself in the pipeline for grants, awards, and positive attention from the federal government and private funders. Moreover, CFSA leaders also appear believe passionately in the currently dominant orientation.

The allergy to “reactive” services is telling. Many agencies have reactive missions–police, firefighters, emergency rooms–and one could argue these are the most important services of all because they save lives and prevent serious injuries. The analogy with the police cannot be ignored. Police react to allegations of crime just as child welfare agencies react to allegations of child abuse and neglect. To prevent crime, we must not rely on the police, who are overburdened already and not trained and equipped to provide the services needed. Instead we must turn to a whole host of agencies dealing with education, public health, mental health, housing, income security and more–the same agencies that we must mobilize if we want to prevent child abuse and neglect.

It is still interesting to speculate on how the rejection of more hotline reports by hotline workers and the reduced number of referrals to in-home services by CPS workers has been (and is being) accomplished in practice. Both the acceptance of referrals and the assignment of a risk level are governed by actuarial assessment instruments. But as a former social worker in the system, I know that these instruments can be completed so as to obtain the desired response. Perhaps that is the answer or perhaps the instruments have been changed. I wish the Council’s oversight committee for CFSA would ask the agency this question.

CFSA’s data for FY2023 provide new evidence that the agency is withdrawing from its primary mission of protecting children who have already been abused or neglected in favor of reaching out to families that have not been reported to the agency. This is particularly evident from the decrease in referrals accepted for investigation, the decreasing proportion of open cases as a percentage of substantiations, and the increased emphasis on serving, through the collaboratives and the family success centers, families that are not currently involved with CFSA. With total budgetary resources decreasing, there is reason to fear that abused and neglected children are less protected every year as CFSA spreads its resources more and more thinly.

Notes

*While the number of referrals accepted for investigation was 3,902 in FY2023 according to the Dashboard’s Hotline Calls by Referral Type graphic, the total number of investigations displayed in the Investigations by Disposition graphic was 3,704. The reason for the difference is unclear. According to the Dashboard, “accepted for investigation” means that “the hotline call resulted in a new investigation being opened on the family.” So the two numbers should be the same.

**Such an informal placement may occur before substantiation as well.

***These data do not exactly agree with numbers that I have collected from the CFSA dashboard over the years. I have also noticed that Dashboard data for the same period, particularly in-home case data, has changed over time.

**** It appears that those with an open CFSA case qualify as Front Porch families if they are receiving collaborative services as well as in-home services from CFSA, but this is confusing and suggests the agency may be double-counting families by counting them in both the “in-home” and “front porch” populations. The agency cites a different definition of Front Porch families in its 2023 Annual Public Report, saying that the term refers to “families that have already been the subject of a CPS investigation but did not present with safety or risk levels that warranted opening a child welfare case.

Every year, the DC Council’s Committee on Human Services, currently chaired by Councilwoman Brianne Nadeau, submits a series of detailed oversight questions to the Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA). These questions focus on many aspects of the agency’s operations and policy. The lengthy

Every year, the DC Council’s Committee on Human Services, currently chaired by Councilwoman Brianne Nadeau, submits a series of detailed oversight questions to the Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA). These questions focus on many aspects of the agency’s operations and policy. The lengthy