Good afternoon! Thank you for the opportunity to testify today. My name is Marie Cohen and I live in Ward 6. After my first career as a policy analyst and researcher, I became a social worker and served in the District’s child welfare system until 2015. Soon after leaving that job, I joined the Citizen Review Panel on CFSA, on which I served for four years, and then the Child Fatality Review Committee, on which I served for six years. I began writing a blog, which later became Child Welfare Monitor. I am proud to say that my blog is read by some of the leading policymakers, advocates, and academics in the field. I take a child-centered approach, placing the safety and wellbeing of the child above all other considerations.

On October 22, 2022, police were called to Stanton Road, SE, for a report of an unconscious child. By the time they arrived, Journey McCoy had already been transported to United Medical Center, where she was pronounced dead.[i] According to WUSA-9, Sasha McCoy, the child’s mother, reported that around 8:30 a.m. her daughter came from the back bedroom of the house and said she was hungry. McCoy gave her a Jell-O cup and went back to sleep. Around 1 p.m. she was awakened to two of her four children rummaging in the refrigerator. Instead of feeding them she put both children down for a nap and went back to sleep on the couch. Such reports of parents sleeping through their children’s days, without regular bedtimes or mealtimes, are classic symptoms of what child welfare experts call chronic neglect. Sometime later, Ms. McCoy woke up again and found her child unconscious with yellow mucus coming out of her mouth.

On October 22, 2022, police were called to Stanton Road, SE, for a report of an unconscious child. By the time they arrived, Journey McCoy had already been transported to United Medical Center, where she was pronounced dead. According to WUSA-9, Sasha McCoy, the child’s mother, reported that around 8:30 a.m. her daughter came from the back bedroom of the house and said she was hungry. McCoy gave her a Jell-O cup and went back to sleep. Around 1 p.m. she was awakened to two of her four children rummaging in the refrigerator. Instead of feeding them she put both children down for a nap and went back to sleep on the couch. Such reports of parents sleeping through their children’s days, without regular bedtimes or mealtimes, are classic symptoms of what child welfare experts call chronic neglect. Sometime later, Ms. McCoy woke up again and found her child unconscious with yellow mucus coming out of her mouth.

During the ensuing investigation, police learned that Sasha McCoy, was known in her neighborhood for using drugs and being constantly high. McCoy admitted to using Percocet daily, including the morning of the day her daughter died. When the CFSA investigator offered her a referral to drug treatment she responded, “this is not the time. I am going to get high as a “mother f-er when I leave.” Seven months later, the autopsy came back. The cause of death was fentanyl intoxication. McCoy was arrested and charged with first degree felony murder and cruelty to children. During the fatality investigation, CFSA and police learned that the mother was living with a known drug dealer. She admitted to the use of unprescribed drugs, which she failed to secure away from the children. The dead child’s sibling has been placed in foster care.

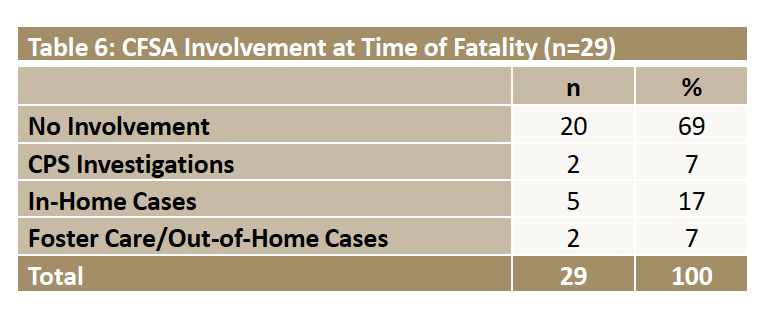

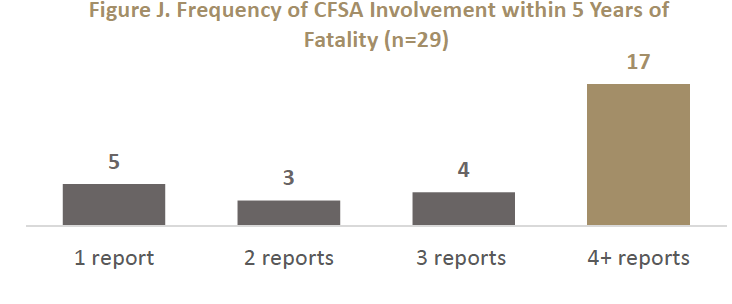

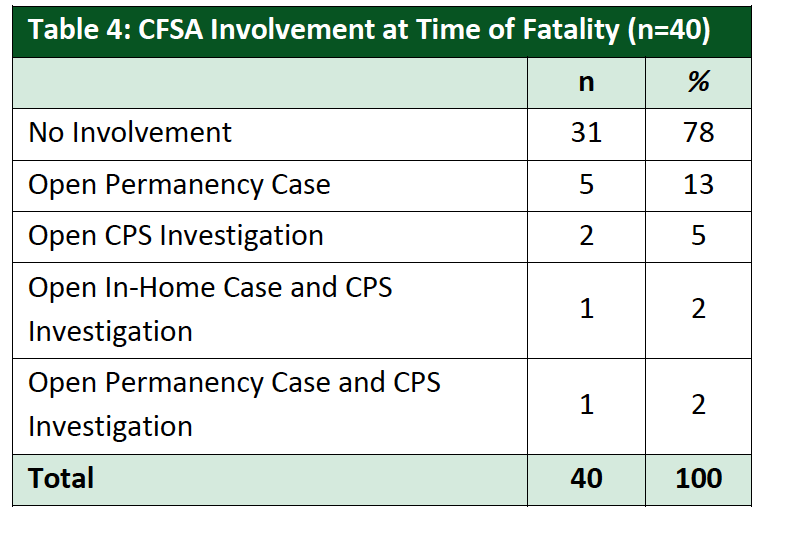

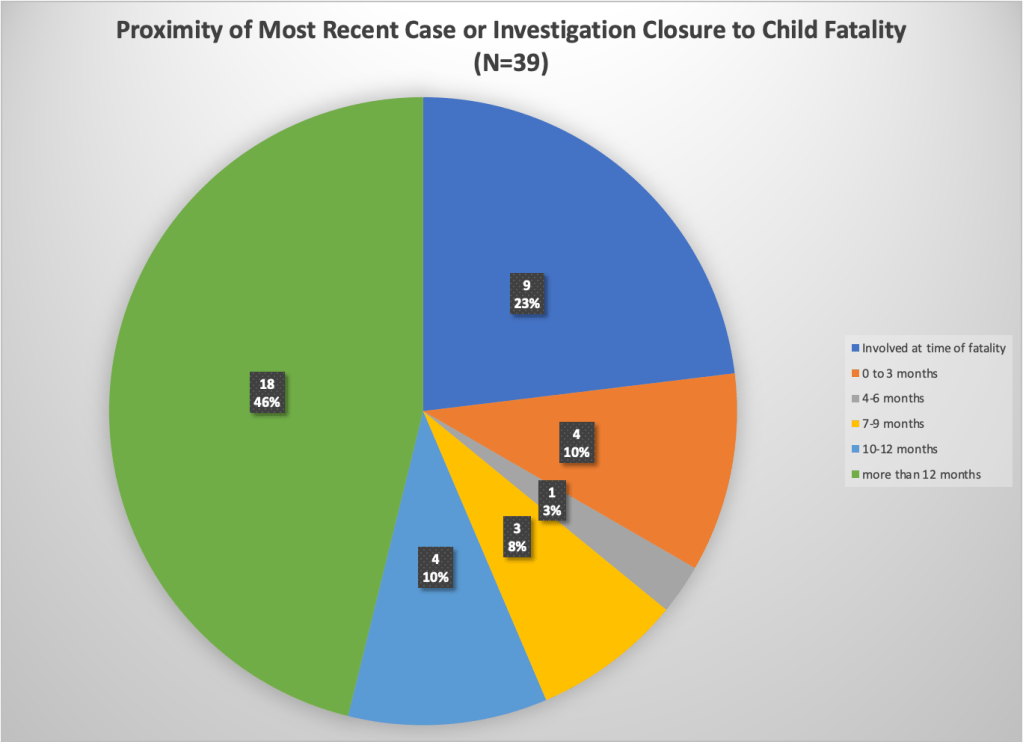

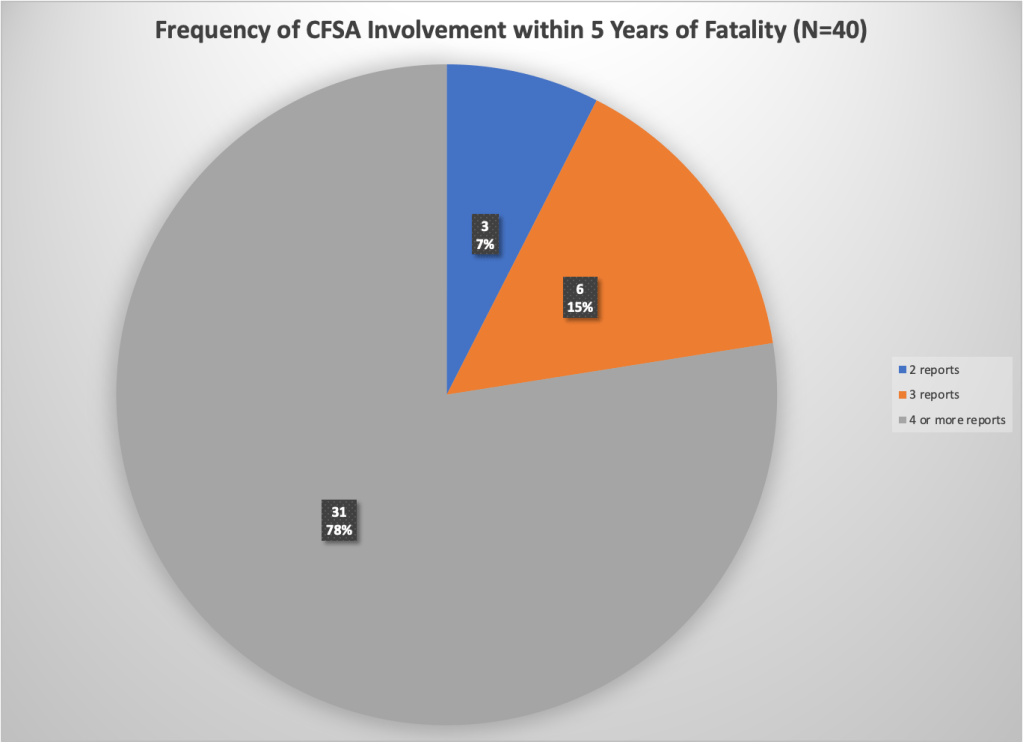

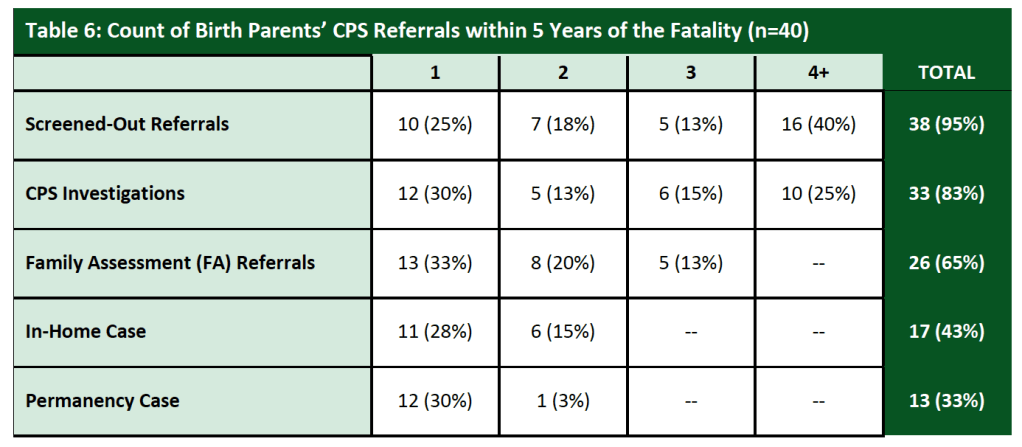

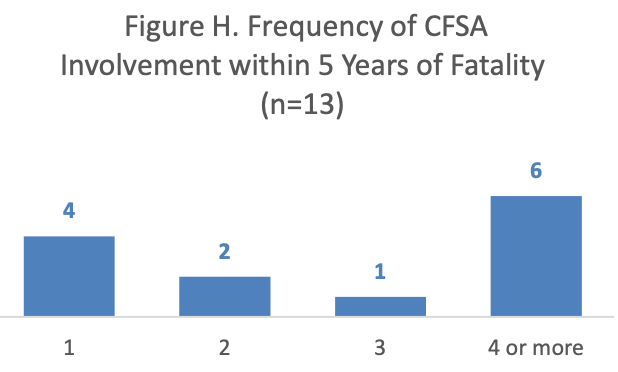

CFSA knew about McCoy before her daughter’s death, as described in the agency’s newest annual fatality report, which focuses on deaths of children in families known to CFSA in the previous five years.[i] Within five years of the three-year-old’s death, the family had three CPS investigations, one family assessment, and two open in-home cases. According to WUSA9, one of these cases was opened in 2020 when the same little girl as a baby ingested marijuana at a party McCoy was hosting. Social workers found three children unsupervised inside the home. The case was eventually closed. Another case was opened In August 2021 after McCoy’s newborn had symptoms of withdrawal. McCoy acknowledged using Percocet daily throughout her pregnancy. That case remained open until February 3, 2022, eight months before the fatality. Surprisingly, the agency did not observe any evidence of drug use or concerns for supervision during the two open in-home cases. (This is hard for me to believe, unless the mother evaded social worker visits, as happened with many of the cases I reviewed.) Nevertheless, CFSA reported that “case notes indicated the mother resisted the Agency’s efforts to engage her and she was inconsistent with participation in services.”

“We are not here to save children.” That is what I was told on the first day of my training as a child protective services worker at CFSA. And indeed, the District of Columbia is on the cutting edge of the current movement in child welfare that considers child protective services as a “family policing system” that unnecessarily harasses and separates families, especially families of color. But some families do not provide a safe environment for children to grow and develop. In some of these families, children die. That is what happened to the 16 children whose cases are discussed in my recently released report.

Why do I study fatalities among children known to CFSA? For the same reason that CFSA studies these deaths. As the agency states in its 2023 Annual Child Fatality Report, seeing where the system may have broken down helps it identify strategies that may prevent such deaths in the future, which is why the agency makes recommendations at the end of these reports. But it is more than that. The same conditions that lead to child fatalities also lead to harm for many more children. In that sense, child fatalities are the tip of the iceberg of child maltreatment, giving us a window on what is happening to other children who may be invisible to us.

The report is based on information I received from CFSA on the deaths of 16 children between 2019 and 2021—before the death I described earlier. These children came from families that had previous contact with CFSA. Their deaths were either ruled to be caused by child abuse or neglect or the Medical Examiner could not rule out child abuse or neglect as contributing to the cause of death.” District law requires the release of information on these deaths, but CFSA interpreted that law restrictively. Several deaths were not included because they were ruled to be accidents, although parental neglect clearly contributed to these deaths. For example, the death of seven-week-old Kyon Jones, whose mother told police that she threw his body in a dumpster after she rolled over him while high on PCP, was not included because his body was never found and could not be autopsied. A child was left in a baby swing for two hours was also included because his death was deemed accidental.

In addition to omitting some cases in which neglect or abuse played a role, CFSA heavily redacted the information it did provide, with many pages and large blocks of text blacked out. This included most information about the parents’ issues with drugs, alcohol, or mental health and almost the entire history of agency involvement in most cases. Despite the limited information provided, the redacted summaries included some disturbing new information.

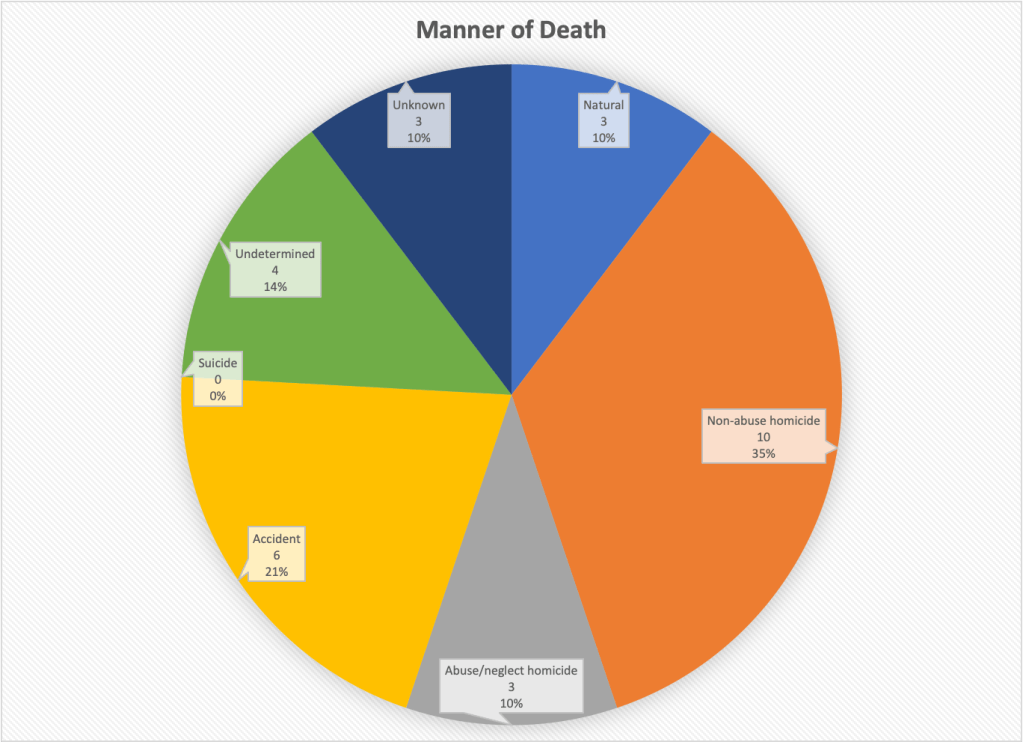

Causes of Death

The most common causes of death among the 16 children were blunt-force trauma and opioid poisoning, each claiming the lives of three children. This included Makenzie Anderson, who was murdered by her mother, and Gabriel Eason, who was the victim of long-term torture and beatings by his stepfather, as his mother stood by. The third case of blunt-force trauma was a three-year-old girl in the home of an aunt where she was placed by CFSA. Nobody has been charged for this murder. Another three children (a three-year-old girl, a three-year-old boy, and a three-month-old girl) died of poisoning by a controlled substance, with fentanyl implicated in all three cases. The remaining children died from drowning, asphyxia, “thermal and scald injuries,” injuries from a car accident, and unknown causes, a few of which may not reflect maltreatment.

Demographics

A quarter of the children who died were younger than six months old and half were one year old or younger. Another quarter were two or three. This is not surprising as young children are more vulnerable and similar results are found nationally. But older children were not invulnerable to abuse or neglect, including the seven-year-old who died in a car accident and a 12-year-old who died of an untreated bacterial infection and pneumonia.

All of the decedents were Black: fifteen were African American and one was classified as “African-biracial.” According to the latest data from Kids Count, 54 percent of children in the District of Columbia are Black. So Black children were overrepresented among the children who died of maltreatment or possible maltreatment. Yet, the District is trying to reduce racial disparities in system involvement. It sounds to me like a way to make Black children less safe, not more equal.

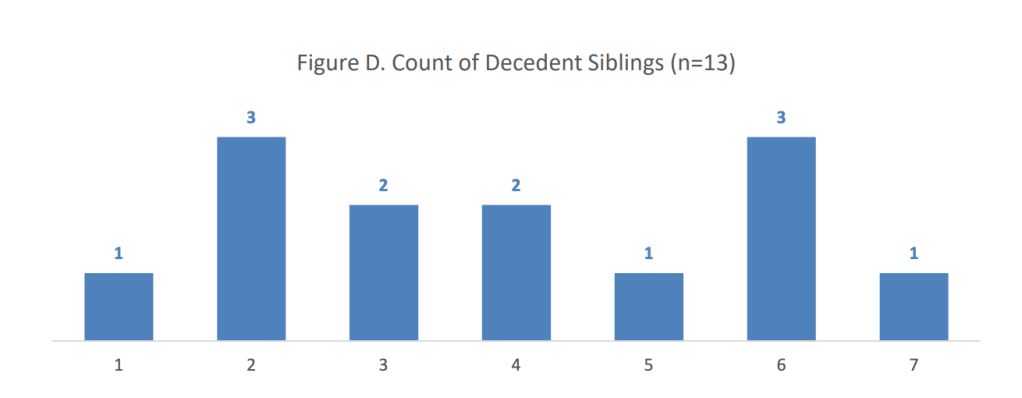

The prevalence of large families among those that lost a child due to abuse or neglect is striking, though not surprising, because research shows that large families are associated with child maltreatment. More than two thirds of the mothers of children who died by maltreatment had four or more children. The average mother in the group had 4.6 children, often with more than one father. This is not surprising, because larger number of children are associated with child maltreatment. The challenges of parenting multiple children clearly contribute to a child’s risk of being abused or neglected and dying of that maltreatment.

Histories of System Involvement

Most of the families that lost a child had experienced multiple reports prior to the fatality. Among the 16 fatalities included in this report, only six occurred in families that were the subject of five reports or fewer in the last five years. Five occurred in families that had between six and 10 reports, three occurred in families with 10 to 15 reports, and one family had 24 reports. Three of the families had experienced a previous child fatality–a shocking statistic considering the rarity of child fatalities overall.

Substance abuse by the parent or caregiver (including positive toxicology of a newborn) was the most frequent allegation CFSA received regarding the families in the five years before the deaths. Substance abuse by the parents was observed or alleged in the families of all but four of the victims included in this report. Inadequate supervision and educational neglect were the next most common. Ten of the 15 families had at least one report for educational neglect and ten for inadequate supervision before the child’s death. Another major theme was exposure to domestic violence, which was mentioned in nine of the 16 case histories as the subject of an allegation or in notes from social workers or police.

A 17-month-old boy died of “thermal and scald injuries.” His mother had no idea how he got injured. She said he was sleeping on the floor next to her bed when she went to sleep at 7:00 PM, but he often slept next to the radiator in the living room because she kept the air conditioning on high and he got cold. She reported that one of her five other children woke her at about 3:00 AM and showed her large pus bubbles on the child’s thigh and lower leg. She told the girl to bring him to another room and planned to clean the wound in the morning, for fear of being reported to CFSA. She reported having no idea why he was found in the bathtub with his face down at about 7:00 AM.

System Failures

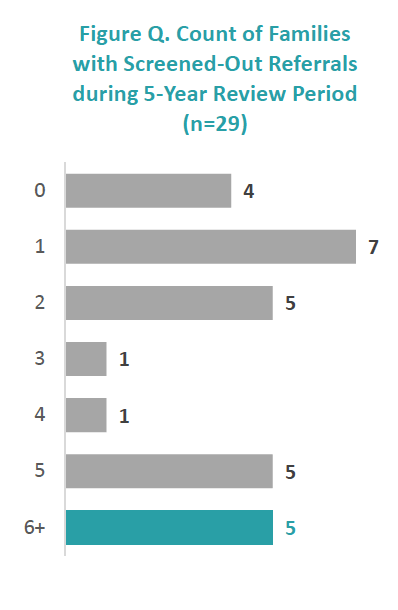

The information received suggests several areas where failures in policy and practice by CFSA may have allowed these deaths to happen. These areas include screening and investigation. Many reports on these families were screened out hotline staff, perhaps inappropriately. The Office of the Ombudsperson for Children (OFC) reports that it received complaints from constituents about referrals that were screened out inappropriately; OFC itself had concerns about several referrals that were screened out. OFC also heard from school staff who reported receiving no feedback after submitting multiple reports on the same family.

Flawed investigations may have also allowed these fatalities to happen, as these families had many unsubstantiated investigations. The details of most investigations were completely redacted, so I cannot give many examples of possible flaws. But Gabriel Eason, who was beaten to death by his stepfather, was the subject of an investigation five months before his death, after he showed up at childcare with two bruised ears. The CPS investigator did not seem concerned about the mother’s lack of knowledge of how the injury was acquired, her offering of multiple possible explanations, and the question of how playing rough with his siblings on running into furniture could result in bruises on both sides of his face.

Management of in-home cases was revealed by these fatalities as an area of concern for CFSA. Four of the deaths I reviewed here happened while an in-home case was open for the family, yet in three of these cases, workers struggled to complete face-to-face visits with the families because parents evaded these visits. Three other families had had one or more in-home cases that closed before the children were killed. In the Needs Assessment it recently released, CFSA focused on its in-home services and found little evidence for optimism about their potential to help children. By caseworkers’ own assessment, the most common barriers that caregivers display (daily parenting behavior, substance abuse, and mental health) barely change between the opening and closing of an-In-Home case. Only a quarter of the In-Home cases reviewed by CFSA’s internal reviewers, demonstrated good progress according to these reviewers, despite the good clinical skills of the social workers. CFSA concluded that the lack of progress in the other three-quarters of cases was due to the lack of parental engagement in services.1 CFSA’s oversight responses show that of the 503 in-home cases closed in FY 2023 and the first quarter of FY 2024, 214 (or 40%) of the families were the subject of a hotline call after the case was closed.

In the three open cases where parents evaded social worker visits, social workers and supervisors could have used the “community papering” option to file a petition to involve the court. But they did not exercise this option–or they started too late. In one case, a three-year-old had been left alone on her stomach with a bottle while her mother went across the street to retrieve and smoke a cigarette. During the in-home case resulting from that fatality, the case manager made multiple unsuccessful attempts to see the mother and her three surviving children. Due to the mother’s failure to engage and the children’s continued absence from school, the case manager scheduled a meeting with legal staff to consider community papering. That meeting was scheduled for December 8, 2021 and was canceled after CFSA learned of the three-year-old’s death of fentanyl poisoning on December 3.

In the FY2025 Needs Assessment, CFSA stated that “[h]istorically, QSR reviews have shown that parents’ active participation and engagement in services, and their ambivalence to work with the Agency, remain a challenge for the In-Home Administration. Despite training inevidence-based skills [such as motivational interviewing] social workers continued to face multiple challenges for achieving positive outcomes. . . Challenges for the social work team and the families included complicating factors such as unresolved (or insufficiently addressed) family histories of trauma, substance use, mental illness, cognitive challenges, and parenting capacity with multiple children.

Recommendations

- The Council should change the law to mandate release of Information on child maltreatment fatalities. Sadly, CFSA’s internal fatality committee, which reviewed the full record of these cases, does not do a good job of making recommendations. The 2022 report had no recommendations for CFSA other than it should participate in districtwide discussions about violence prevention; its other recommendations referred to other agencies, like better information sharing and a safe sleep campaign. We certainly cannot rely on CFSA to learn from its mistakes. Therefore, my first recommendation is to the City Council, urging it to require that CFSA follow the example of states like Florida, Arizona, and Wisconsin, andrelease detailed historical information on child fatalities, with certain identifying information redacted.

- CFSA should Improve the hotline and investigations through training and specialization: I endorse the OFC’s recommendation for enhanced training for hotline staff so that reports are screened adequately to ensure the safety of children. In addition, school absences should be investigated regardless of the age of the child (requiring a change in the law) and their academic performance. Investigative workers could benefit from better training in forensic interviewing techniques that might help them better evaluate parents’ and children’s’ statements for veracity and perceive more subtle signs of abuse or neglect. Another option is to reinstate the Special Abuse Unit so that cases of physical and sexual abuse are handled by workers with forensic interview training.

- CFSA must recognize that in-home cases need to be more intensive and longer for chronically neglectful families: CFSA must also strengthen its in-home practice, perhaps by reinstating the Chronic Neglect Units, which were eliminated barely a year after they were implemented. These units would employ specially trained social workers with lower caseloads and longer time periods to work with families.

- The agency must reduce any barriers to the use of “community papering,” perhaps making court involvement routine after a certain number of missed visits or other instances of noncooperation, or if a family that is offered in-home services after an investigation refuses the offer. The case narratives make clear that social workers struggled to complete home visits to the families of the children who later died, and yet community papering was either not initiated, or initiated too late. According to the recent Needs Assessment, the agency presented over 300 children with in-home cases for community papering in FY 2021, FY2022 and the first quarter of FY2023.[iii] But my study suggests that these petitions must be made sooner and more often.

It is often said that we should not make policy based on extreme cases. But I have a different view. Extreme cases are the tip of the iceberg. Every child who dies, represents multiple other children who are suffering or at least failing to thrive as they live with abuse or neglect. Studying fatalities can help identify system failures that allow many more children to languish in abusive or neglectful homes, growing up in fear or pain, or without the essential nurturing necessary for normal child development.

- CFSA also found that when an In-Home case is opened, a family’s risk of child removal decreases by 15 percent within a year. But the likelihood of a new investigation increases by 10 percent within the year. CFSA speculates that perhaps the subsequent Investigation ends up prolonging the in-home case by starting a new In-Home episode.