“We are not here to save children.” That is what I was told on the first day of my training as a child protective services worker at the District of Columbia’s Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA). And indeed, the District is on the cutting edge of the current movement in child welfare around the country that considers child protective services as a “family policing system” that unnecessarily harasses and separates families, especially families of color. The problem with this perspective is that some families do not provide a safe environment for children to grow and develop. In some of these families, children die. That is what happened to the 16 children whose cases are discussed in a new report, which is summarized in this post. And indeed, analysis of the limited information provided suggests that CFSA did not take advantage of the opportunities it had to protect children even after long histories of CFSA involvement in their families. As a result, three children were beaten to death, three more were poisoned by opioids, and others died of burns, a car accident, and unknown causes when the deaths might have been preventable if the agency had been more protective.

When a child dies of abuse or neglect after that child’s family has been on the radar of the agency designed to protect children, it is important for the public to know whether and how this death could have been avoided. The essential question is whether the agency could have prevented the death by doing something differently. Did staff miss any red flags, and therefore fail to take action when necessary? If the death was preventable, what factors must be remedied in order to prevent such failures in the future? It is not enough for the agency itself to have access to this information, or to have an internal team review it. Agencies can fail to learn from their mistakes when they are blinded by ideology, self-interest or just inertia.

For those reasons, federal law requires every state to have a law or program that includes “provisions which allow for public disclosure of the findings or information about the case of child abuse or neglect which has resulted in a child fatality or near fatality.” In compliance with this requirement, DC Code requires the Mayor or the Director of CFSA, upon written request or on their own initiative, to provide findings and information related to “[t]he death of a child where the Chief Medical Examiner cannot rule out child abuse, neglect, or maltreatment as contributing to the cause of death.” In March 2023, we requested such findings and information for all the fatalities that met the criteria and were reviewed by CFSA’s internal fatality review team between 2019 and 2021. It took more than six months of meetings and emails to receive the information that is presented in this report. We agreed to restrict our request to cases reviewed in 2019, 2020 and 2021 and to withdraw our request for information on near-fatalities, which CFSA only began tracking in October, 2022.

Not surprisingly, CFSA interpreted the disclosure requirements in a way that restricted the information provided as much as possible. If a medical examiner did not rule the manner of death to be an abuse or neglect homicide or “undetermined,” no information was provided. Therefore, the agency did not release any information on cases where the manner of death was labeled as accidental, even if it found a parent responsible for the death or removed the children. The “accidental” deaths for which information was not provided included one child who died after he was left in a baby swing for two hours, which most ordinary people would consider to be neglect. The death of seven-week-old Kyon Jones, whose mother told police that she threw his body in a dumpster after she rolled over him while high on PCP, was not included because his body was never found and therefore it did not meet the criteria for release of the information–even though CFSA removed the surviving children from their mother.*

In addition to omitting some cases in which neglect or abuse played a role, CFSA heavily redacted the information it did provide, with many pages and large portions of others blacked out. CFSA refused to provide the names of the children, parents and caregivers, providing a rather convoluted interpretation of DC Code, which clearly requires the release of this information. (See the full report for more information about their reasoning). In three cases, the child’s identity was clear from media coverage of the case, and we used the child’s name. A major source of redactions was the exclusion of “personal or private information unrelated to the child fatality.” It appears that CFSA’s legal team interpreted this term much more broadly than a social worker or researcher would, because they redacted almost all information about parents’ history of criminal activity, substance abuse, mental illness, and domestic violence–which are obviously relevant to many of the fatalities we are discussing.

On investigations, it is unfortunate that DC Code requires that the agency release only ”a description of the conduct of the most recent investigation or assessment” rather than all investigations regarding the family in question. It appears that the agency interpreted “the most recent investigation” as the fatality investigation itself rather than the most recent investigation before the fatality, but the law ought to require a description of all previous investigations. The agency also disregarded language that requires it to provide “the basis for any finding of either abuse or neglect.”

For most cases, we received very little information aside from a list of the previous referrals (reports to the CPS hotline) including only the date of the report, the allegation category and the disposition; an account of in-home and foster care case activities for the families that had such cases; and an account of the investigation of the fatality itself. The information about the parents was heavily redacted, and almost the entire history of agency involvement was blacked out in most cases. Despite the limited information provided, the redacted summaries included some new information, some of which was startling and disturbing. The report is based on the 16 case summaries provided by CFSA, occasionally supplemented with information from the agency’s annual fatality reports, which are available to the public. These cases affected 15 families, as one family had two fatalities in one year. Unless otherwise noted, the information is based on the case summaries. The full report, from which this blog is excerpted, contains summaries of each case.

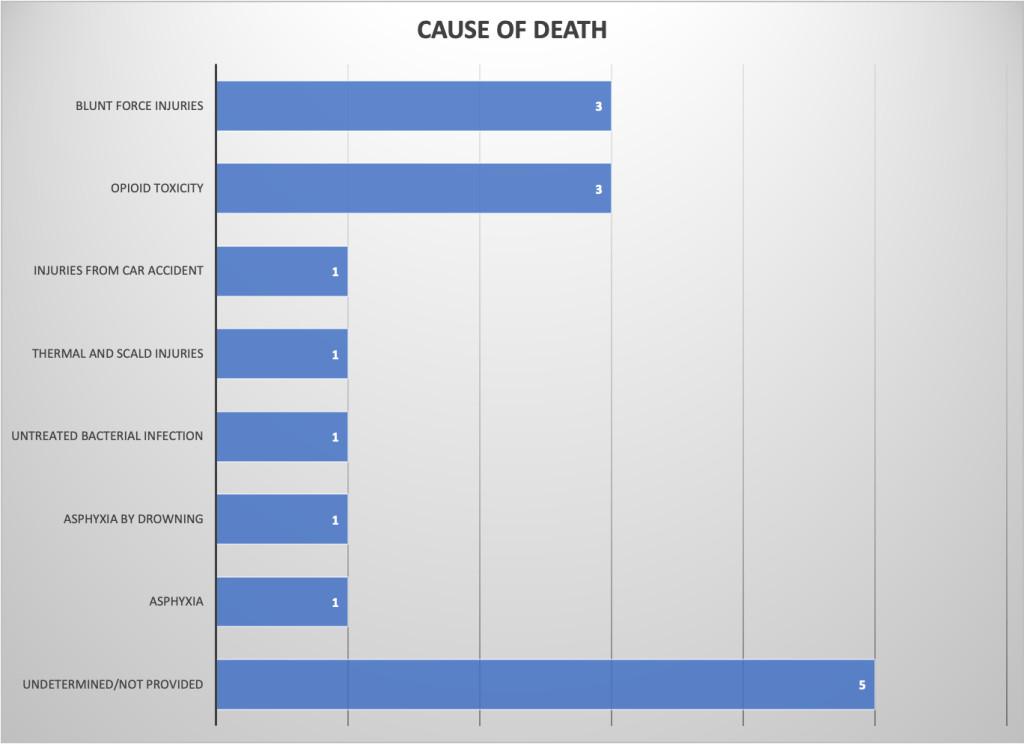

Cause and Manner of Death

CFSA classifies child deaths by cause and manner. “Cause of death” is the specific disease or injury that led to the death. Manner of death refers to the circumstances that caused the death, and falls into five categories: natural, accidental, suicide, homicide, and undetermined. Of the 16 cases for which information was provided by CFSA, three (19 percent) were abuse homicides, six (37 percent) were neglect homicides, and seven (44 percent) were undetermined in manner. The latter were the cases for which CFSA provided information because the Medical Examiner was unable to rule out child abuse or neglect homicide as the manner of death.

The most common causes of death were blunt-force trauma and opioid poisoning, each claiming the lives of three children, as shown in figure below. The remaining children died from a variety of causes, including drowning, asphyxia, thermal and scald injuries, injuries from a car accident, and unknown causes.

Abuse deaths: Blunt Force Trauma

Three of the children died of blunt force trauma–one of the two most common causes of death in the sample. The murders of two of these children – Makenzie Anderson and Gabriel Eason – – became known to the horrified public through press coverage of their deaths in February and April of 2020. Each of them died from head trauma inflicted by a parent or stepparent. Makenzie suffered from multiple contusions to the face and head, skull fractures, and other injuries, and her mother pleaded guilty to manslaughter, receiving a ten-year prison term with seven years suspended on the condition that she obtain mental health treatment and have no unsupervised contact with children. Gabriel’s autopsy found abrasions and contusions to the head, face and torso; contusions to the heart and thymus gland; liver and kidney laceration; new and healing fractured ribs; and a brain hematoma. His stepfather was sentenced to 12 years and eight months in prison and his mother, who did not seek medical help for Gabriel or his critically-injured three-year-old brother, was sentenced to four years of probation and three years of supervised release.

But there was a third homicide by blunt force trauma. A three-year-old girl died of trauma to the abdomen in the home of an aunt where she was placed by CFSA after being removed from her drug-addicted mother. Her injuries included contusions to the forehead and abdomen, a lacerated liver, and blood in the abdominal cavity. No charges were filed against either the aunt or her boyfriend, and the case received almost no public attention.

Neglect deaths: Opioid Poisoning and other causes

Three children (a three-year-old girl, a three-year-old boy, and a three-month-old girl) died of synthetic opioid toxicity, with fentanyl implicated in all three deaths. (One of the children had also ingested a controlled substance called eutylone.) There is no information about how the children might have ingested the drugs, but all lived with parents who were known or alleged to abuse substances. These deaths never became known to the public, which is not surprising since it appears that none of the parents were arrested or charged.

A 17-month-old boy died of “complications of thermal and scald injuries,” and his mother told the investigator that she had no idea how it happened or how he ended up face-down in the bathtub several hours later. A seven-year-old died of injuries from a car accident. His mother was a long-time substance abuser and was arrested for Driving Under the Influence (DUI) in the accident. She was driving from Florida to Washington and her children were not sitting in car seats or belted in. A five-month-old boy died of asphyxia by drowning after being left alone in the bathtub with a one-year-old sibling while their mother searched for her car keys.

Deaths for Which the Manner was Undetermined

Two deaths has known causes but the manner – whether abuse or neglect or something else – was not determined. A twelve-year-old girl with asthma died of an untreated bacterial infection and pneumonia but also had enough bruising from two separate beatings in the previous two days to support a CFSA substantiation of the mother for physical abuse. It is unclear why this was not considered a medical neglect homicide. A ten-month-old girl died of asphyxia but the manner of death was undetermined. Her mother had left her in the care of her father and returned to find her unresponsive.

The cause as well as the manner of death was unknown or undetermined in five cases. These included an 18-month-old boy with a subdural hematoma, which could have been caused by abuse or a fall, an 11-month-old girl whose mother reported leaving her unsupervised on her stomach with a bottle in her mouth for about 40 minutes, a nine-month-old boy put to bed with a bottle and found face-down on a pillow; a two-month-old girl who died while sleeping with her mother, and a three-month-old girl found unresponsive by her parents one morning. Unsafe sleep practices may have contributed to some of these deaths, but other unsafe sleep fatalities were categorized as accidents, for which case summaries were not provided.

Demographics

A quarter of the children who died were younger than six months old and half of them were one-year-old or younger. Another quarter were two or three. This is not surprising as young children are more vulnerable and similar results are found nationally. But older children were not invulnerable to abuse or neglect, including the seven-year-old who died in a car accident and the 12-year-old who died of an untreated bacterial infection and pneumonia.

Fifteen of the decedents were African American and one was classified as “African-biracial.” According to the latest data from Kids Count, 54 percent of children in the District of Columbia are Black. So Black children were overrepresented among the children who died of maltreatment or possible maltreatment. The overrepresentation of Black children among children who died points to Black children’s particular need for protection. And it suggests that current emphasis in the District and around the country on reducing the involvement of Black families in child welfare may cause more suffering and more deaths among Black children.

The prevalence of large families among those that lost a child due to abuse or neglect is striking. More than two thirds of the mothers of children who died by maltreatment had four or more children. The average mother in the group had 4.6 children, often with more than one father.

Histories of System Involvement

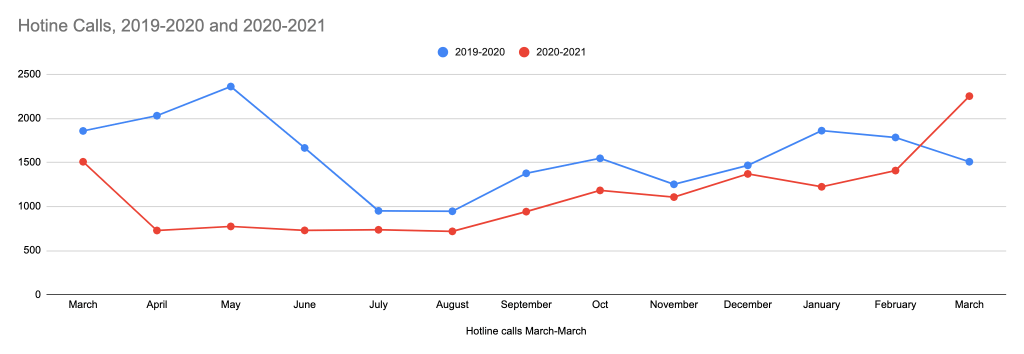

All the families had been the subject of at least one report to the CFSA hotline before the fatality, or else they would not be included in this report. But many of the families that lost a child had experienced a large number of reports prior to the fatality. Among the 16 fatalities included in this report, only six occurred in families that were the subject of five reports or fewer in the last five years. Five occurred in families that had between six and 10 reports, three occurred in families with 10 to 15 reports, and one family had 24 reports. Three of the families had actually experienced a previous child fatality–a shocking statistic considering the rarity of child fatalities overall.

The families of the two children – Makenzie Anderson and Gabriel Eason – whose abuse homicides shocked the District of Columbia in February and April 2020 were both known to CFSA before the deaths, and the last report to the hotline came five months before the fatalities of both children. Makenzie Anderson’s family was reported to the hotline eight times within five years of her death. The last report alleged exposure to unsafe living conditions, inadequate supervision, and substance abuse by a parent, caregiver, or guardian. All those allegations were unfounded (not confirmed) by CFSA. Gabriel Eason’s family was the subject of 17 prior calls to the hotline since 2012, including 12 in the five years preceding Gabriel’s death. The most recent report was for unexplained physical injury in October 2019 and was also unfounded by CFSA.

Substance abuse by the parent or caregiver was the most frequent allegation CFSA received regarding the families in the five years before the deaths, with 30 substance abuse allegations collectively accumulated by the families of the 16 dead children during that period. Another eight reports concerned positive toxicity of a newborn, a reflection of parental substance abuse. Substance abuse by the parents was observed or alleged in the families of all but four of the victims included in this report. Inadequate supervision was the second most common allegation, with 25 allegations concerning the 15 families. Almost as common was educational neglect, referring to children with excessive school absences, with 24 allegations received in the five years preceding the fatality. Ten of the 15 families had at least one report for educational neglect before the child’s death. Another major theme was exposure to domestic violence, with 17 allegations received by the families. Domestic violence was mentioned in nine of the 16 case histories as the subject of an allegation or in notes from social workers or police.

Most of these families could be described as “chronically neglectful.” According to the Child Welfare Information Gateway, “Chronic child neglect occurs when a caregiver repeatedly fails to meet a child’s basic physical, developmental, and/or emotional needs. Chronic neglect can have long-term, negative consequences for child health and well-being.” Working with chronically neglectful families is especially difficult and requires special training and skills, which many CFSA social workers may lack. Perhaps that is one reason why they struggled so hard to engage some of these families. Four of the children died while an in-home case was open. Three out of four of the in-home case narratives from CFSA portray caregivers who evaded offers of help from CFSA and other providers and refused to cooperate with efforts to monitor conditions in their homes.

System Failures

The information received suggests several areas where failures in policy and practice by CFSA and other agencies may have allowed these deaths to happen. These areas include:

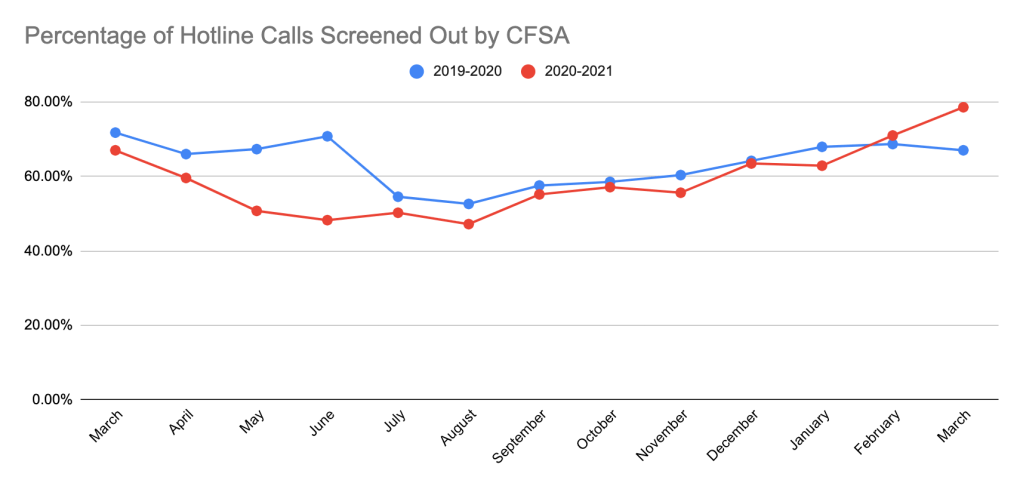

- Screened out and unsubstantiated reports: Research points to the difficulty of determining correctly whether a child has been maltreated, as well as the absence of significant differences in subsequent outcomes between children with a substantiated allegation of maltreatment and those with an unfounded allegation. Without information on how hotline and investigation decisions were made, we cannot assess the agency’s performance in these areas. But the fact that most previous reports for families with a subsequent death were screened out or unfounded is concerning.

- Flawed management of in-home cases: Four of the deaths reviewed here happened while an in-home case was open for the family. In three of these cases, workers struggled to complete face-to-face visits with the families because parents evaded these visits. Social workers and supervisors could have filed a petition to involve the court, an option known as “community papering.” But they did not exercise this option–or they started too late, as in the case of the child who died after a meeting was finally scheduled to discuss community papering the case. The meeting was cancelled after the agency received word of the child’s death.

- Too many chances: The mother of the seven-year-old killed in the 2020 car accident had been given numerous chances to recover from drug addiction and had relapsed many times over 18 years of involvement with CSFA. The family of the 17-month-old who died of complications of thermal and scald injuries had 24 referrals to CFSA between 2016 and 2021. Three in-home cases were opened and closed, but the children were not removed until the little boy died.

- A fragmented health care system: In its findings on Gabriel Eason’s death, CFSA pointed out that Gabriel was taken to different medical providers for his various injuries. Because they use different information systems, the providers could not see records of the earlier injuries.

The reaction of CFSA and the criminal justice system after the fatalities obviously did not contribute to the fatalities themselves but may illustrate a pattern that contributes to future deaths. Specifically, CFSA’s tendency to place siblings informally after fatalities and the police and US District Attorney’s failure to charge parents raise concerns.

- Informal placements after fatalities: CFSA, and child welfare agencies around the country, have been criticized for relying on informal placements with family members, rather than formally removing the children, placing them with the relatives, and opening a case to monitor their safety and well-being. In at least four of the 16 cases reviewed here, CFSA did not officially remove the siblings of the children who died but instead relied on informal placements with fathers or other relatives to keep them safe. Nothing was done to assure that the children were not returned to the home from which they had been removed as soon as the investigations closed, or to verify that the parents or caregivers had rectified the conditions leading to the child deaths.

- Failures by the criminal justice system: The failure to bring charges against some of the parents and caregivers described here is quite concerning, particularly in the case of the three-year-old who died of blunt-force trauma and the infant and two three-year-olds who died of opioid poisoning. There has been considerable criticism of the US Attorney’s office in the District (which handles adult criminal prosecutions) for its low rate of opting to charge people for crimes. We do not know if the problem is the Metropolitan Police Department’s failure to bring the cases to the US Attorney or the latter’s failure to pursue them.

Recommendations

Without seeing the full case studies that were available to CFSA’s internal review committee, we cannot make detailed recommendations about how to avoid child maltreatment fatalities for children known to CFSA. The minimal recommendations that CFSA’s internal review team made show the need for the City Council, advocates and the public to have access to these complete case studies. Therefore, our first recommendation is to the City Council, urging it to require that CFSA release comprehensive case histories on all proven or suspected child maltreatment fatalities: in its 2021 report the agency made no recommendations other than those dealing with the fatality review process! . Our next blog post will discuss the legislative changes that are needed.

The lack of information on how screening and investigation decisions in particular were made precludes specific recommendations. Perhaps a new audit of the hotline is in order. Some changes to hotline screening policy might be advisable, especially around educational neglect. School absences should be investigated regardless of the age of the child (requiring a change in the law) and their academic performance. And perhaps investigative workers could benefit from better training in forensic interviewing techniques that might help them better evaluate parents’ and childrens’ statements for veracity and perceive more subtle signs of abuse or neglect.

The case narratives make clear that in-home social workers struggled to complete home visits to the families of the children who later died. The agency must change its policy to encourage “community papering,” making court involvement routine after a certain number of missed visits or other instances of noncooperation. CFSA might also want to consider strengthening its in-home practice, perhaps by reinstating the Chronic Neglect Units, which were eliminated barely a year after they were implemented. These units would employ specially-trained social workers with lower caseloads and longer time periods to work with families.

Despite the current ideology favoring family preservation and reunification at all costs, the agency must also recognize that sometimes it must give up on a parent and find a safe, permanent alternative for the children. Giving parents multiple chances with successive children over many years belies the true purpose of child welfare services – to protect children.

Not all needed changes fall in CFSA’s bailiwick. Reforms in the criminal justice system are also necessary to ensure that parents who killed one child cannot harm more children. Couples who refuse to cooperate with prosecutors, and parents who expose children to opioids due to their own abuse or drug dealing must also be charged. Other jurisdictions do it, and the District must do it as well.

DC Health and medical providers also have a crucial role to play in making children safer. Encouraging the adoption of a comprehensive medical information platform across the region to prevent families from using different doctors to hide abuse and neglect would be a welcome step. A campaign by DC Health to educate young women on how an early pregnancy, especially when followed quickly by others, compromises their future and that of their children, is a crucial necessity. It must be accompanied by improved access to long-acting reversible contraceptive methods.

In summary, even with the very minimal information we received, some conclusions emerge. CFSA’s extreme deference to parents and guardians emerges clearly through the redactions in these narratives. This is in direct contrast to the picture that is being painted by the foundations, advocacy groups and public agencies dominating the child welfare conversation. Their accounts portray interventionist child welfare agencies that remove children rather than giving their families the help they need and want. We are seeing the opposite here: families who evade offers of help from the agency and providers and refuse to cooperate with efforts to monitor conditions in the home. The goal of such parents often appears to be to avoid surveillance by outsiders rather than to improve their ability to care for their children. And CFSA workers often seem unwilling or unable to intervene in a way that will protect these children.

‘The tragic deaths of children whose families are known to CFSA are the tip of a much larger iceberg. For every child who dies of abuse or neglect, an unknown number of others are living in fear or pain from abuse, suffering chronic neglect that will cause lifelong intellectual an emotional damage, or lacking the loving attention necessary for optimal mental, emotional and physical development. Sadly, it is only the children who die whose cases can be used to learn lessons to prevent similar tragedies in the future. This information must be public, so that the public can push for a system that protects all children who are not receiving the parental care they need to survive and thrive.

*The case, which received media coverage, was included and easily identifiable in