In the public testimony on the CFSA budget, there were pleas from several speakers to increase funding for home visiting programs funded by CFSA. So I did a little digging to determine how the current funds are being spent, and what I found was rather shocking. In Fiscal Year 2022 (FY22), CFSA handed over $330,000 to the DC Department of Health, to serve a grand total of 33 families, of whom only 16 completed the program. The agency spent another $360,000 to serve an unknown number of families in home visiting programs that have not been shown to reduce child maltreatment. The generic acceptance of home visiting programs as prevention against all ills appears to be part of the problem; the lack of sufficient options under the Family First Act appears to be another.

First some context. Home visiting is not a program, but rather a service delivery strategy that can be used in many different programs. There are many, many home visiting program models with different goals, services, staffing, and target populations. According to the website of the DC Home Visiting Council, the District currently offers 16 home visiting programs, each with different goals and supporting different needs. There is evidence supporting the impact of some of these programs on certain outcomes, but “home visiting” itself is neither a program nor evidence-based, despite multiple statements to the contrary at the CFSA budget oversight hearing on April 12, 2023.

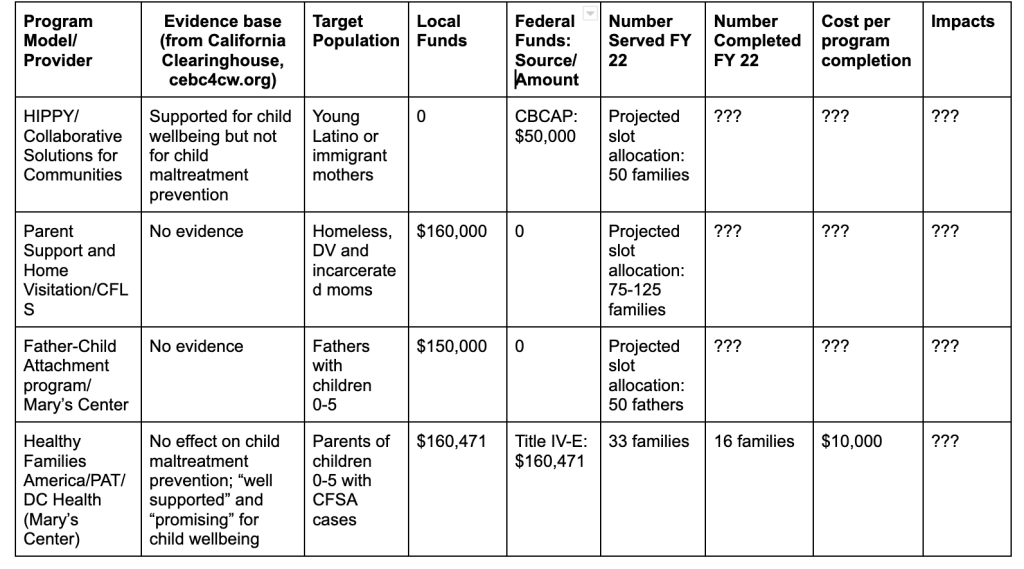

CFSA supports home visiting programs for two different populations using two different funding streams–Community-based Child Abuse Prevention Grants (CBCAP) and Title IV-E of the Social Security Act. Through CBCAP, CFSA funds three home visiting programs for “primary (universal) prevention“1 of child abuse and neglect before it occurs. CFSA uses Title IV-E funds to pay for services to families known to the agency but who may not have a substantiated allegation or an open case. These funds are transferred to the DC Department of Health (DOH) to pay for slots in two home visiting program models, Healthy Families America and Parents as Teachers, both delivered by Mary’s Center) to this population.

The CBCAP”primary prevention” programs

Programs/Clientele: In 2022, CFSA paid three providers directly for programs under CBPAP. Collaborative Solutions for Communities provided Home Instruction for Parents of Preschool Youngsters (HIPPY) to young Latino or immigrant mothers with children aged 0-6; Community Family Life Services provided “Parent Support and Home Visitation”2 to mothers who were homeless, formerly incarcerated, or affected by domestic violence; and Mary’s Center provided a “Father-Child Attachment program”2 to “fathers with children (0-5) deemed at risk.”

Evidence Base: Given the name of the funding source (Community-based Child Abuse Prevention Grants) it would be reasonable to expect that the programs funded would have evidence showing that they prevent child maltreatment. Yet, there is no evidence that any of the programs CFSA funds under this stream reduces child maltreatment. HIPPY is an education-focused program designed to prepare children for success in school and beyond. It is not listed by the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (CEBC), the nation’s leading child welfare clearinghouse, as a home visiting program for prevention of maltreatment. Neither “Parent Support and Home Visitation” nor “Father-Child Attachment” are listed in the clearinghouse and neither appears to be a tested model. Moreover, CFSA provides no information about program outcomes in its oversight responses.

Funding: In 2022, CFSA spent $50,000 on HIPPY, $160,000 on “Parent Support and Home Visitation” and $150,000 on the “Father-Child Attachment program” of Mary’s Center.” The Mayor’s budget does not provide FY23 spending or FY24 requested funding for individual home visiting programs, or even for these programs as a group, and CFSA did not respond when I asked how much it plans to spend this year. But the testimony of DC Action for Children, which lobbies for increases in home visiting funding, suggests that the agency is planning to keep funding level for FY 24.

Number of people served: In its oversight responses, CFSA provided no information on the number of people who were actually served last year by these three programs – only the “projected slot allocation” provided in the table: 50 mothers for HIPPY, 75-125 mothers for CFLS, and 50 fathers for Mary’s Center. FY22 ended on September 30, 2022, so the agency should have been able to report on how many people were served. But CFSA Director Robert Matthews did testify that there is excess capacity in all these programs, so we can assume that fewer than the 175-225 slots allocated were filled.

The DOH programs funded by Title IV-E

Programs and Clientele: CFSA transfers Title IV-E funds to the Department of Health (DOH) in exchange for providing two home visiting programs, Parents as Teachers (PAT) and Healthy Families America (HFA), to eligible families. Potential participants include families known to CFSA but who may not have a substantiated allegation or an open case, as described in CFSA’s Title IV-E Prevention Plan. This includes families receiving services from a collaborative following a CFSA investigation or closed case; families of children who have exited foster care but are at risk of re-entry; families of children born with postive toxicology; families receiving CFSA in-home services; pregnant and parenting youth in foster care or recently exited from foster care, and their children; and siblings of children in foster care.

Evidence Base: In order to be allowable uses of Title IV-E funding, programs must have been approved as Evidence-Based Practices (EBP) by the Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse, which was created by the Family First Prevention Services Act of 2017 (“Family First”). Family First allowed Title IV-E funds, previously available only for foster care, to be used for services to prevent a child’s placement in foster care. For a program to be approved, the Clearinghouse must find that a evaluation meeting its criteria determined that the program had at least two impacts on any of seven different target outcomes.3 Unfortunately, the programs do not have to demonstrate reductions in child maltreatment, though logic suggests that such reductions would be necessary to prevent placement in foster care. Both PAT and HFA have been approved by the clearinghouse as EBP’s. But neither of these programs was found to produce meaningful reductions in child maltreatment.4 One reason may be that, as evaluations have shown, home visiting programs “have struggled to enroll, engage and retain families.”

Funding: CFSA funnels $160,471 in local funds and approximately the same amount in federal TItle IV-E funds to DOH to pay for these two programs, which are delivered by Mary’s Center. According to the oversight responses, this is done through a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) “which “pays for 40 slots of the PAT model to specifically serve the…. families defined in CFSA’s Title IV-E Prevention Plan. In addition to these 40 PAT slots, the MOU also outlines how CFSA, and DC Health will partner to ensure the child welfare agency is referring families to HFA and PAT whenever appropriate, regardless of candidate eligibility under Family First.” This is confusing. Services to families not eligible under Family First cannot legally be funded using Title IV-E so it is not clear how Title IV-E could be used to provide them.

The missing MOU: In its FY23 oversight questions to CFSA, the Facilities and Family Services Committee requested all MOU’s currently in place or planned. Those MOU’s are listed on page 148 of the Oversight Attachments. There was no CFSA-DOH MOU listed as in place as of January 23, 2023 but there was one “In Process” that dealt with “coordination around home visiting.” That is very odd, given that CFSA referred twice to an existing MOU in its responses describing the home visiting programs provided by DOH. I requested the DOH MOU from CFSA on April 21 and have received no response or explanation. Quite possibly, there is still no MOU in effect.

Numbers Served and Cost: According to the oversight responses, CFSA referred 105 families to PAT and HFA in FY22, of whom only 33 families were served and 16 completed the programs, as shown in the table. The large dropoffs from referral to service and from service to completion are not surprising in view of CFSA Director Robert Matthews’ remarks at the budget oversight hearing. Explaining why the agency did not need more funding for home visiting, Matthews said that CFSA is not allowed to mandate participation in home visiting and that many CFSA parents do not want to participate in these programs. And it is highly plausible that the ones who do are those who need it least. At a cost of over $160,000 each in local and federal funds to serve only 33 families of whom only 16 completed the program, it looks like CFSA spent about $10,000 per program participant and $20,000 per program completer in PAT and HFA . That would be a scandal. But it is also possible that the money paid for home visiting for additional parents who were not eligible for Title IV-E funding. And that would be illegal.

Learning from the past? FY22 was not an outlier. In FY21, CFSA reported only 26 families served out of 159 referred to Mary’s Center for home visiting programs funded under Title IV-E. One might think that once CFSA saw how few of its clients were participating in FY21, they would have amended their Title IV-E plan and substituted other services for PAT and HFA. After all, CFSA said in its oversight responses that “work completed in FY22 to refer families to these services was, and will continue to be, analyzed to determine ongoing service needs for Family First target populations.” It is hard to understand how this kind of analysis would have resulted in the continuation of current funding levels for these unpopular services.

Questions and Possible Answers

Why is CFSA spending so much money on home visiting programs that are unproven to prevent child maltreatment and not popular among target families? One possible answer, most relevant to the three programs funded through CBCAP, stems from the history of home visiting. Modern home visiting was developed as a child maltreatment prevention program, and there was great hope after some initial results that appeared promising. But once the programs were rigorously evaluated, the results were disappointing. The possible exception was the Nurse Family Partnership (NFP, formally known as the Nurse Home Visiting Program). NFP was the only program shown to reduce child maltreatment using objective measures other than maternal self-reports, and it also had other impressive effects. But NFP, the only program to use nurses as home visitors, is more difficult to implement and is restricted to first-time teen mothers, and its most impressive results were achieved for White teen mothers in rural New York state. Other programs like HFA and PAT, which were easier to implement, grew more and faster, perhaps benefiting from the excitement about NFP. It was in the interests of most of the programs (and the researchers who specialized in evaluating them) to portray “home visiting” as one undifferentiated program model, allowing programs with less encouraging results to benefit from the success of their more promising peers.

One reason for the widespread use of Title IV-E funds on home visiting programs may be the lack of available alternatives. The passage of the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) in 2017 was hailed as a breakthrough for allowing the expenditure of Title IV-E funds, formerly used only for foster care, to be used for “prevention services” aimed at keeping families together. But as one essential article points out, rigid standards and administrative burdens have crippled the law’s ability to have an impact on the availability of services. Between the requirement that programs be approved by a clearinghouse as EBP’s, and the prohibition of using IV-E funds for services funded by Medicaid, jurisdictions did not have much choice (particularly in the early days of the law) if they wanted to claim federal Title IV-E dollars for “prevention services.” CFSA’s struggle to find appropriate and allowable programs that already existed in the District is made clear in its TItle IV-E Prevention Plan. Of the seven approved programs CFSA chose to implement, four were already funded by Medicaid. PAT and HFA were already being provided by DOH, which made them an attractive option for CFSA. CFSA is claiming Title IV-E funds for only three programs, two of which served only a handful of families. And CFSA is no exception. Nationwide, only 6,200 children in the whole country received a Title IV-E funded “prevention service,” for a grand total of $29 million, in FY 2022.

In light of all these concerns, I believe that CFSA should re-evaluate the home visiting programs it funds based on their effectiveness in preventing child abuse and neglect–and the likelihood that parents will choose to participate. I also believe that Title IV-E funding for HFA and PAT should be eliminated or reduced drastically. Some funds might be diverted to programs that have more recently been approved for Title IV-E funding. With the desperate need among CFSA parents for mental health and drug treatment services, CFSA should consider funneling more funds to the Department of Behavioral Health to purchase such services for its clients.

CFSA’s continued spending on home visiting regardless of purpose, numbers served, interest to families, or effectiveness in preventing maltreatment, may stem from the general misconception about home visiting as an all-purpose prevention program, as well as the lack of choices available under the Family First Act. But CFSA’s spending of Title IV-E funds in particular raises serious concerns. Not only is CFSA wasting resources but it may be diverting Title IV-E funds to an ineligible population–running the risk of having to return funds and possibly receive a penalty from the federal government. And if it is not doing that, then it is spending an unconscionable $20,000 for each person who completes the program.

Notes

- While CFSA describes these programs as “primary (universal) prevention” in its oversight responses, they are actually not universal programs. Instead, they are “secondary prevention” services that target at-risk groups.

- CFSA listed both these programs as “home visiting” with no program title in its oversight responses, but these program names were provided in the testimony of DC Action for Children.

- The seven target outcomes are Child Safety, Child Permanency, Child Well-Being, Adult WellBeing, Access to Services, Referral to Services, and Satisfaction with Programs and Services. A program needs only two positive “contrasts” (out of as many as 80 or evem more different contrasts) between the intervention and comparison group to be approved.

- The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (CEBC), the leading child welfare clearinghouse, does not list either of these programs as Home Visiting Programs for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect. The Title IV-E clearinghouse found that PAT had two very small (5% of a standard deviation), not statistically significant effects on substantiated maltreatment and neglect. The only child safety outcome for which HFA had a positive impact was self-reported (by parents) maltreatment, not a very reliable measure. In contrast, HFA had no effect on child welfare administrative reports. HFA also had no effect on any comparison of maltreatment risk assessment or medical indications of maltreatment risk.

On October 29, 2019, the Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA) became the first child welfare agency to have its Title IV-E Prevention Plan approved by the federal Administration on Children and Families (ACF). This plan, called

On October 29, 2019, the Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA) became the first child welfare agency to have its Title IV-E Prevention Plan approved by the federal Administration on Children and Families (ACF). This plan, called